Rooted in the concept of the human body's operating system, DOHEE KIM's work spans installations, performances, and photography. Her practice encompasses a wide range of themes, including existential uncertainty, conventional portrayals of mortality, the vulnerability of the marginalized, and the journey of women through childbirth. Kim adds a layer of science-fiction-inspired imagination to this reality. In her vision, the birth of a human signifies the simultaneous disappearance of their counterpart in the 'other world,' symbolized by the concepts of plus (+) and minus (-). Kim's work serves as a catalyst for the audience to contemplate their own existence. It offers a sense of solace, assuring us that we are perfectly whole, just as we are. Whether in this world or the greater unknown, there will always be a complementary presence to fill the void.

Dohee Kim has held her solo exhibitions at various venues, including Insa Art Place, Seoul (2011); Jean Art Gallery, Seoul (2017); CR Collective, Seoul (2020); and Kim Hee Soo Art Center, Seoul (2022). Her work has been featured at many group exhibitions, including the 2022 Busan Biennale; Gangwon Triennial 2021; and the 10th Yeosu International Art Festival. In 2021, Kim was awarded the Grand Prize by the Soorim Art Prize. Her work is in the collections at the Soorim Cultural Foundation, Seoul; the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul; the Busan Museum of Contemporary Art, Busan; and the Suwon Museum of Art, Gyeonggi.

I am curious to know what sparked your interest in the operating system of our bodies, the fundamental idea of your practice, and what it means to you.

During my childhood, there was a time when I was sick and had to stay in bed for a while. At the time, I began to wonder if I really existed in this world. It was during this time that I began to question my own existence. I would often experience a sense of uneasy déjà vu when I looked at my two big toes, unsure if they truly belonged to me. I could feel myself if I moved my toes deliberately, but the doubts about my existence that I felt when I stood still are always in my memory. This experience led me to recognize the conventional nature of how I perceived myself. I realized that our sense of 'self' is fluid and depends on the ever-changing conditions we find ourselves in. Starting from this realization, I began creating works that engage with my body both physically and conceptually.

![Dohee Kim, The Beach Under the Skin, 2017. Ground walls. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of 2022 Busan Biennale, Busan. Courtesy of the artist]()

You've worked on a wide range of themes and subjects. I'm curious how you select the material for each motif and subject.

For me, I need to experiment with my body in order to truly make an artwork my own. I find genuine satisfaction in it. To truly experience my work, I actively involve my body in the process. I make a conscious effort to avoid the use of artificial ingredients. For instance, despite my background in painting, I have only produced one painting in which I applied paint to a canvas on the wall. Artificial materials simply don't resonate with me. Instead, I have a preference for raw, natural, and everyday materials.

The Beach Under the Skin (2017), featured at the 2022 Busan Biennale, alludes to the concept of labor among many other aspects of our bodies. It was fascinating to see you create new patterns on the gallery wall by directly grounding it and revealing the accumulated layers of paint that had built up over the years, similiar to ‘kangkangee’* work. Could you please provide more details regarding the work, including the process and the utilization of the central motif, the concept of 'kangkangee'?

I didn't originally focus on labor as the central theme of my work. I was born and raised in Kangkangee, a village in Yeongdo, Busan, by my grandparents. Growing up there, the sounds of the shipyard near my home, the various industrial factory odors in the vicinity, the waves of the Yeongdo Sea, and the vitality of the land imprinted themselves on my very being. From a young age, I had wanted to create a piece inspired by 'kangkangee,' much like the shipyard workers.

At the same time, I started to think about the formation process of my body prior to my solo exhibit, Root of Tongue, at Jean Art Gallery in 2017. It became clear to me that the sensations I experienced in my youth shaped my body, and these very sensations could serve as a medium for my art. I wanted to reflect on my experiences in Yeongdo. I was able to carry out the ‘kangkangee’ directly on the gallery wall, which I later exhibited at the Busan Biennale as well. Throughout the process, I found it difficult to visibly discern the 'kangkangee' marks on the wall due to the dust. It is really the vibration and sound of working that I can remember instinctively, rather than the image. As you mentioned, the process of creating this work was essentially the artist's labor, if we were to consider artistic acts as labor.

*The word ‘kangkangee’ comes from the sound of a hammer hitting the surface of the ship to strip away old and rusty paint or shells at the shipyard.

![Dohee Kim, Bed Wetting, 2014. Boy's urine on paper. 840 x 300 cm. Courtesy of the artist]()

![(detail)]()

It was interesting to see your direct use of breast milk in Moon Illusion (2012) and urine in Bed-Wetting (2014), featured at the Young Korea Artists exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. Why did you choose to directly use both materials instead of substituting them with materials of similar color and texture?

When I was invited to participate in the Young Korea Artists exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in 2014, I was skeptical about the art scene. In an age when we are bombarded with images, I began to wonder what it meant for me to create new images or artworks and what lasting impressions they could leave on the audience after only a few seconds or minutes of viewing. This idea inspired me to create art that would immobilize the senses of the viewers, allowing them to contemplate my work in depth. I believe that artwork that elicits such sensations and some sort of physical reaction has the potential to create 'physical challenges' in audiences. These physical challenges are merely meaningful events. That's why my early works were intentionally unpleasant.

In Moon Illusion, I wanted to depict the white and shiny breast milk, as well as the remarkable vitality and liveliness that it possesses. Because the milk was left unattended for an extended period of time at the exhibition, insects were born in it, and their vivid presences made me realize that life and death can only be distinguished from a specific point of view.

![Installation view of Tummo at Kim Hee Soo Art Center, Seoul, 2022. Courtesy of Kim Hee Soo Art Center and the artist]()

![Installation view of Tummo at Kim Hee Soo Art Center, Seoul, 2022. Courtesy of Kim Hee Soo Art Center and the artist]()

I would like to know more about the concept of death and life that has been prominently featured in your body of work since the beginning. Has your experience of giving birth affected your perspective on life, birth, and death?

After going through certain personal experiences, I started thinking about how death can be misleading, realizing it's more complex than it seems. I also faced the idea that our emotions often pull us into the temporary nature of life. As I mentioned earlier, my childhood doubts about my own existence became more intense when I experienced several deaths in my life.

After giving birth, I reflected on the complex relationship between myself and others. I had a magical experience watching my child grow and transform into a distinct individual while dealing with the confusing notion that my child, who had thrived with sole blood, may or may not be an extension of myself.

This experience sparked my interest in the navel and became an inspiration for Volcano Peak (2018–ongoing). When you think about it, the belly button sticks out when it's connected to the mother, but if that connection is severed, it retracts to become the navel we have now. I incorporated the idea of plus (+) and minus (-) into this concept, which led to a sci-fi fantasy. It's like the moment we were born, we simultaneously vanished from another world in which we used to exist and showed up in the real world. We became a plus in one world and a minus in the other.

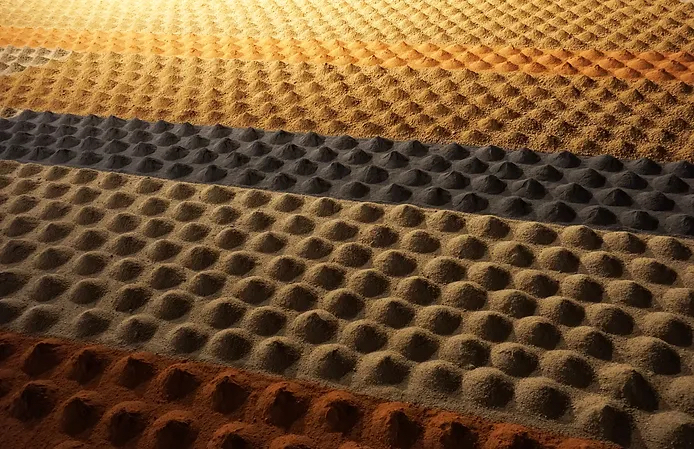

![Dohee Kim, Yungneung for All People, 2019. Korean soil. 820 x 820 cm. Courtesy of the artist]()

![(detail)]()

Yungneung for All People (2019) and Breast Mountain (2022) and are both works in which you used soil to create the same figure. But then why did you give them different names?

I used to climb the mountain frequently and began farming myself, so I naturally wanted to use the soil as a material for my artwork. I found a primitive quality in the soil that resonated with the essence of my work. I made the first soil work, Yungneung for All People, when I was invited to the exhibition with the theme King Jeongjo. However, during the exhibition, I noticed that it formed a nipple shape on the small soil hills because the moisture in the soil drained because it was obtained from nature and was not dried much. I really liked that shape. Suddenly, the heavy quality of this work was relieved, and it became familiar and even vibrant. It was also very interesting to see how the nipple-like shape retained a feminine, moist impression even after the soil was entirely dried. This blurred and transposed the rigid boundary between life and death. So, when I exhibited the same artwork, I decided to name it Breast Mountain.

When I look back at your solo exhibitions, I notice that your installations and works in various media are organically connected within the exhibition. How actively do you get yourself involved in each installation process?

I can be very particular about creating a sense of ‘affectus’ that emerges when each work interacts with the others. My intention is for the audience to harmonize with my works, moving in sync with their own rhythm as they explore the exhibition space, rather than perceiving each piece in isolation. I want the exhibition experience to infuse the viewers with a sense of vitality and perhaps even generate a lingering, wave-like effect within them long after they've departed the space.

For example, during my exhibition at Kim Hee Soo Art Center in 2022, I installed two works, Ganggangsullae and Breast Mountain, both in the shape of a wave, against a single wall in the middle that served as a boundary. Installed around the wall were other works that played the role of sequential amplifiers, like going from a slow to a fast tempo. As the wave shapes of Breast Mountain absorbed sounds, they played as a moderator for the sounds coming out of Ganggangsullae and reminded me of the low-tone bass range given its shape.

In a similar context, I positioned Volcano Peak along the extended horizon of Breast Mountain. The idea was to create a resonance between the minus (-) connotation of the navel and the plus (+) connotation of Breast Mountain, producing a rhythmic interplay of rise and fall.

![Installation view of Signs of Extinction at CR Collective, Seoul, 2020. Courtesy of CR Collective and the artist]()

You also frequently engage with the social and political issues that surround us. How do you decide which particular event to incorporate into your work?

I tend to focus on matters or phenomena that I intuitively perceive as personally connected, or those that evoke deep emotional resonance and touch my life on a profound level. These are often subjects that I find myself preoccupied with, and expressing them through my work becomes the only way to move forward. In essence, I believe that I respond to these issues by contemplating the impact I wish my work to have on society and how it can serve as a means to address my own challenges.

You recently launched a contemporary art magazine called Ttheol. It is interesting that you aim to cover the personal life and sentiment of the artist rather than the obscure language and concepts about art.

I've been collecting and reading vintage art magazines since I was young. Currently, I lead a study group that delves into art journals from the 1950s and onward. In these older periodicals, one can find numerous essays and interviews that provide a window into the contemporary era of that time. They offer vivid anecdotes about artists, avoiding abstract and conceptual language. These writings, rich with intimate experiences, have been a profound source of inspiration for me. They led me to create a magazine that includes writings reflecting the personal sentiments and perspectives of artists and authors.

Dohee Kim has held her solo exhibitions at various venues, including Insa Art Place, Seoul (2011); Jean Art Gallery, Seoul (2017); CR Collective, Seoul (2020); and Kim Hee Soo Art Center, Seoul (2022). Her work has been featured at many group exhibitions, including the 2022 Busan Biennale; Gangwon Triennial 2021; and the 10th Yeosu International Art Festival. In 2021, Kim was awarded the Grand Prize by the Soorim Art Prize. Her work is in the collections at the Soorim Cultural Foundation, Seoul; the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul; the Busan Museum of Contemporary Art, Busan; and the Suwon Museum of Art, Gyeonggi.

I am curious to know what sparked your interest in the operating system of our bodies, the fundamental idea of your practice, and what it means to you.

During my childhood, there was a time when I was sick and had to stay in bed for a while. At the time, I began to wonder if I really existed in this world. It was during this time that I began to question my own existence. I would often experience a sense of uneasy déjà vu when I looked at my two big toes, unsure if they truly belonged to me. I could feel myself if I moved my toes deliberately, but the doubts about my existence that I felt when I stood still are always in my memory. This experience led me to recognize the conventional nature of how I perceived myself. I realized that our sense of 'self' is fluid and depends on the ever-changing conditions we find ourselves in. Starting from this realization, I began creating works that engage with my body both physically and conceptually.

Swipe to see more images

You've worked on a wide range of themes and subjects. I'm curious how you select the material for each motif and subject.

For me, I need to experiment with my body in order to truly make an artwork my own. I find genuine satisfaction in it. To truly experience my work, I actively involve my body in the process. I make a conscious effort to avoid the use of artificial ingredients. For instance, despite my background in painting, I have only produced one painting in which I applied paint to a canvas on the wall. Artificial materials simply don't resonate with me. Instead, I have a preference for raw, natural, and everyday materials.

The Beach Under the Skin (2017), featured at the 2022 Busan Biennale, alludes to the concept of labor among many other aspects of our bodies. It was fascinating to see you create new patterns on the gallery wall by directly grounding it and revealing the accumulated layers of paint that had built up over the years, similiar to ‘kangkangee’* work. Could you please provide more details regarding the work, including the process and the utilization of the central motif, the concept of 'kangkangee'?

I didn't originally focus on labor as the central theme of my work. I was born and raised in Kangkangee, a village in Yeongdo, Busan, by my grandparents. Growing up there, the sounds of the shipyard near my home, the various industrial factory odors in the vicinity, the waves of the Yeongdo Sea, and the vitality of the land imprinted themselves on my very being. From a young age, I had wanted to create a piece inspired by 'kangkangee,' much like the shipyard workers.

At the same time, I started to think about the formation process of my body prior to my solo exhibit, Root of Tongue, at Jean Art Gallery in 2017. It became clear to me that the sensations I experienced in my youth shaped my body, and these very sensations could serve as a medium for my art. I wanted to reflect on my experiences in Yeongdo. I was able to carry out the ‘kangkangee’ directly on the gallery wall, which I later exhibited at the Busan Biennale as well. Throughout the process, I found it difficult to visibly discern the 'kangkangee' marks on the wall due to the dust. It is really the vibration and sound of working that I can remember instinctively, rather than the image. As you mentioned, the process of creating this work was essentially the artist's labor, if we were to consider artistic acts as labor.

*The word ‘kangkangee’ comes from the sound of a hammer hitting the surface of the ship to strip away old and rusty paint or shells at the shipyard.

Swipe to see more images

It was interesting to see your direct use of breast milk in Moon Illusion (2012) and urine in Bed-Wetting (2014), featured at the Young Korea Artists exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. Why did you choose to directly use both materials instead of substituting them with materials of similar color and texture?

When I was invited to participate in the Young Korea Artists exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in 2014, I was skeptical about the art scene. In an age when we are bombarded with images, I began to wonder what it meant for me to create new images or artworks and what lasting impressions they could leave on the audience after only a few seconds or minutes of viewing. This idea inspired me to create art that would immobilize the senses of the viewers, allowing them to contemplate my work in depth. I believe that artwork that elicits such sensations and some sort of physical reaction has the potential to create 'physical challenges' in audiences. These physical challenges are merely meaningful events. That's why my early works were intentionally unpleasant.

In Moon Illusion, I wanted to depict the white and shiny breast milk, as well as the remarkable vitality and liveliness that it possesses. Because the milk was left unattended for an extended period of time at the exhibition, insects were born in it, and their vivid presences made me realize that life and death can only be distinguished from a specific point of view.

Swipe to see more images

I would like to know more about the concept of death and life that has been prominently featured in your body of work since the beginning. Has your experience of giving birth affected your perspective on life, birth, and death?

After going through certain personal experiences, I started thinking about how death can be misleading, realizing it's more complex than it seems. I also faced the idea that our emotions often pull us into the temporary nature of life. As I mentioned earlier, my childhood doubts about my own existence became more intense when I experienced several deaths in my life.

After giving birth, I reflected on the complex relationship between myself and others. I had a magical experience watching my child grow and transform into a distinct individual while dealing with the confusing notion that my child, who had thrived with sole blood, may or may not be an extension of myself.

This experience sparked my interest in the navel and became an inspiration for Volcano Peak (2018–ongoing). When you think about it, the belly button sticks out when it's connected to the mother, but if that connection is severed, it retracts to become the navel we have now. I incorporated the idea of plus (+) and minus (-) into this concept, which led to a sci-fi fantasy. It's like the moment we were born, we simultaneously vanished from another world in which we used to exist and showed up in the real world. We became a plus in one world and a minus in the other.

Swipe to see more images

Yungneung for All People (2019) and Breast Mountain (2022) and are both works in which you used soil to create the same figure. But then why did you give them different names?

I used to climb the mountain frequently and began farming myself, so I naturally wanted to use the soil as a material for my artwork. I found a primitive quality in the soil that resonated with the essence of my work. I made the first soil work, Yungneung for All People, when I was invited to the exhibition with the theme King Jeongjo. However, during the exhibition, I noticed that it formed a nipple shape on the small soil hills because the moisture in the soil drained because it was obtained from nature and was not dried much. I really liked that shape. Suddenly, the heavy quality of this work was relieved, and it became familiar and even vibrant. It was also very interesting to see how the nipple-like shape retained a feminine, moist impression even after the soil was entirely dried. This blurred and transposed the rigid boundary between life and death. So, when I exhibited the same artwork, I decided to name it Breast Mountain.

When I look back at your solo exhibitions, I notice that your installations and works in various media are organically connected within the exhibition. How actively do you get yourself involved in each installation process?

I can be very particular about creating a sense of ‘affectus’ that emerges when each work interacts with the others. My intention is for the audience to harmonize with my works, moving in sync with their own rhythm as they explore the exhibition space, rather than perceiving each piece in isolation. I want the exhibition experience to infuse the viewers with a sense of vitality and perhaps even generate a lingering, wave-like effect within them long after they've departed the space.

For example, during my exhibition at Kim Hee Soo Art Center in 2022, I installed two works, Ganggangsullae and Breast Mountain, both in the shape of a wave, against a single wall in the middle that served as a boundary. Installed around the wall were other works that played the role of sequential amplifiers, like going from a slow to a fast tempo. As the wave shapes of Breast Mountain absorbed sounds, they played as a moderator for the sounds coming out of Ganggangsullae and reminded me of the low-tone bass range given its shape.

In a similar context, I positioned Volcano Peak along the extended horizon of Breast Mountain. The idea was to create a resonance between the minus (-) connotation of the navel and the plus (+) connotation of Breast Mountain, producing a rhythmic interplay of rise and fall.

You also frequently engage with the social and political issues that surround us. How do you decide which particular event to incorporate into your work?

I tend to focus on matters or phenomena that I intuitively perceive as personally connected, or those that evoke deep emotional resonance and touch my life on a profound level. These are often subjects that I find myself preoccupied with, and expressing them through my work becomes the only way to move forward. In essence, I believe that I respond to these issues by contemplating the impact I wish my work to have on society and how it can serve as a means to address my own challenges.

You recently launched a contemporary art magazine called Ttheol. It is interesting that you aim to cover the personal life and sentiment of the artist rather than the obscure language and concepts about art.

I've been collecting and reading vintage art magazines since I was young. Currently, I lead a study group that delves into art journals from the 1950s and onward. In these older periodicals, one can find numerous essays and interviews that provide a window into the contemporary era of that time. They offer vivid anecdotes about artists, avoiding abstract and conceptual language. These writings, rich with intimate experiences, have been a profound source of inspiration for me. They led me to create a magazine that includes writings reflecting the personal sentiments and perspectives of artists and authors.

© 2023 Radar