EOM YU JEONG’s works begin from her meticulous,

keen eyes on our surroundings such as elements in nature, humans, and inanimate

objects. While she is widely recognized for receiving the first prize in the

2021 Best Book Design from All Over the World, Radar sought to approach her

work with a broader perspective, spanning from paintings of melting mountains

in Iceland to animations depicting waves in Jeju Island. Her works have been

shown in A-Lounge Gallery, Seoul (2023); Kumho Museum of Art, Seoul (2023); Hakgojae Design Gallery, Seoul (2021); and Cheongju Art Studio, Cheongju (2019). She is based in Seoul.

Have you always had the aspiration to become a painter?

I’ve always had a deep desire to become a painter since I was very young, too young to even remember when it began. During my undergrad years, however, my school didn't particularly support drawing as a medium, which occasionally left me frustrated. Then, during my period as an exchange student at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore, I experienced a lot of pivotal changes. During my time there, I discovered, for the first time, that even small-sized drawings could be regarded as artworks. With the guidance of a supportive professor and engaging with lectures that differed from conventional painting classes, my perspective began to expand.

Upon returning to Korea, I delved into courses that focused on the human body. This marked the inception of my ongoing project as well as the compilation of a drawing archive featuring human gestures and bodies. It has since served as the fundamental foundation for the artwork I create today.

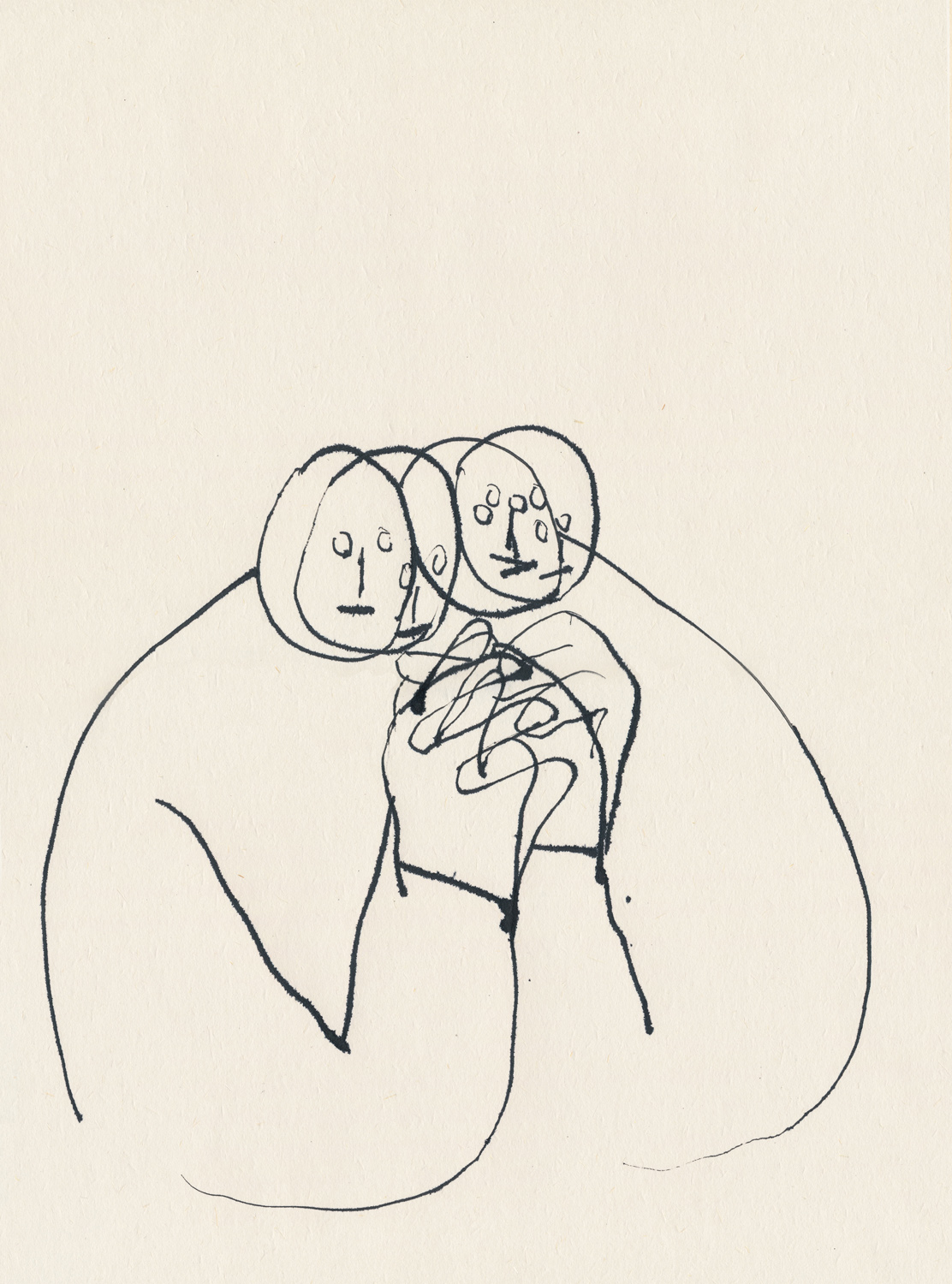

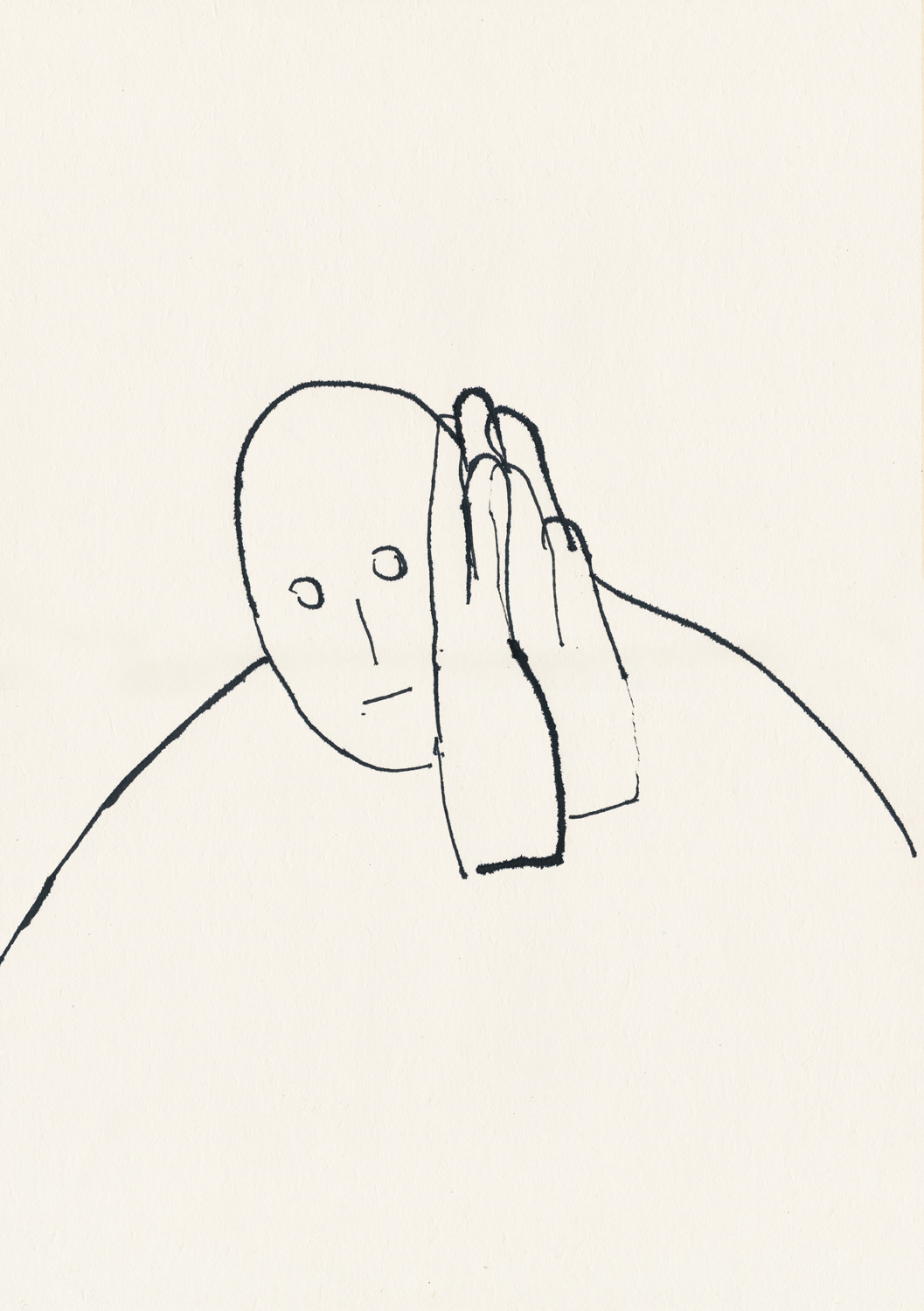

![Eom Yu Jeong, Relationship series, 2012. Color pencil on paper. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Eom Yu Jeong, Relationship series, 2012. Color pencil on paper. Courtesy of the artist]()

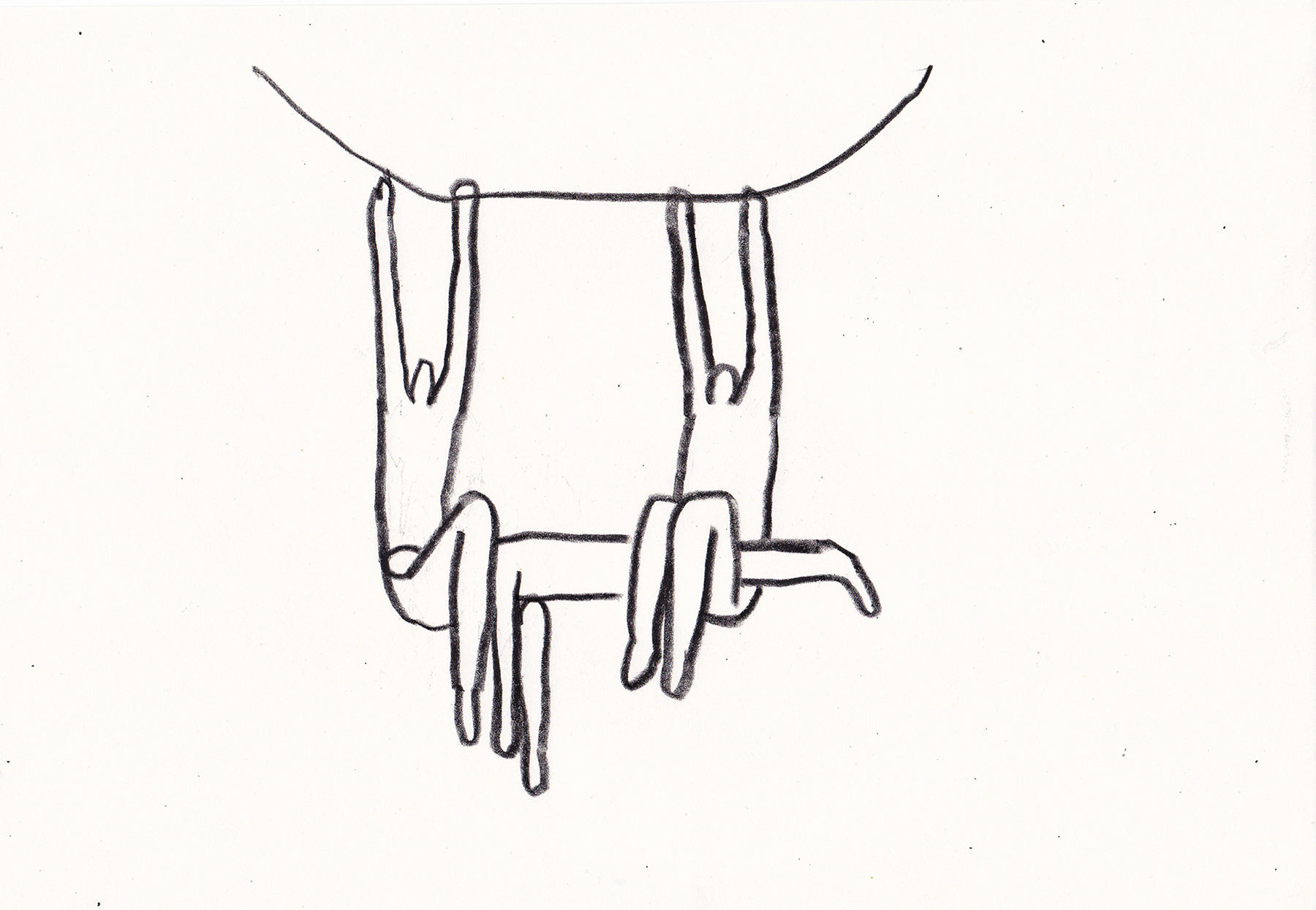

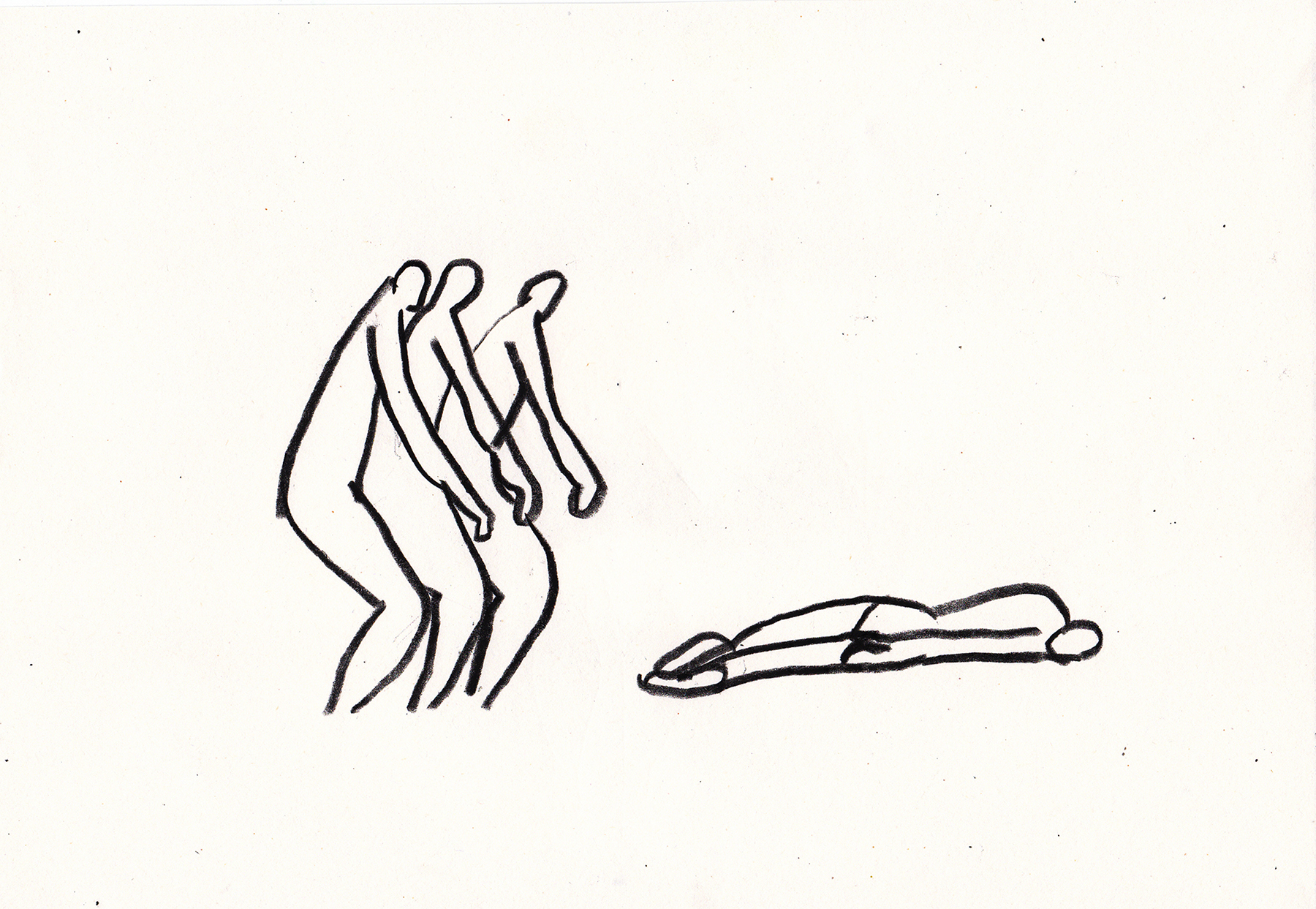

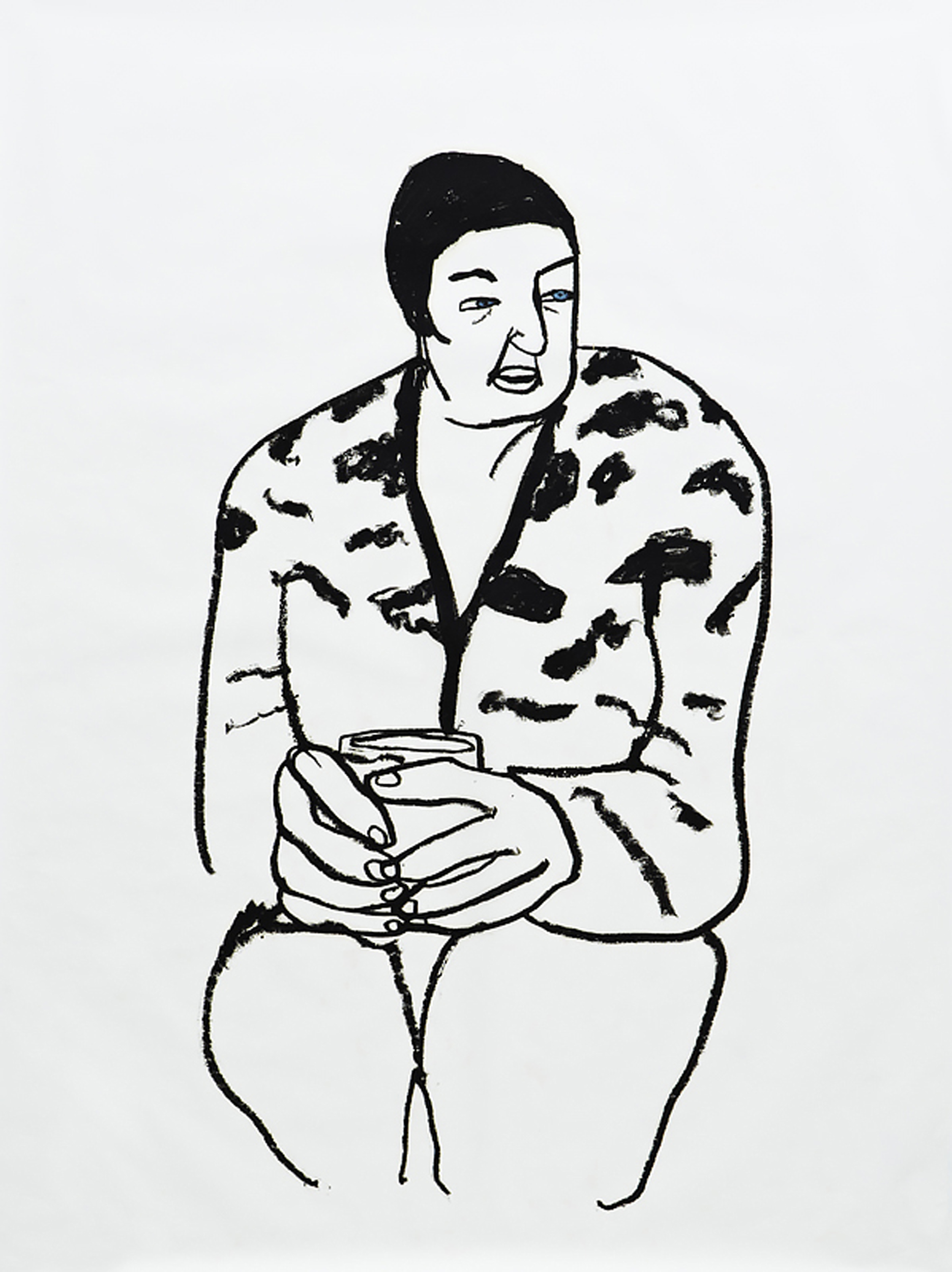

![Eom Yu Jeong, Body series, 2012-14. Pen on paper. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Eom Yu Jeong, Body series, 2012-14. Pen on paper. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Eom Yu Jeong, Fisherman from Iceland series, 2014. Oil color on paper. 109 x 98 cm (42.9 x 38.6 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Eom Yu Jeong, Fisherman from Iceland series, 2014. Gouache on paper. 109 x 98 cm (42.9 x 38.6 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Eom Yu Jeong, Woman from Iceland series, 2014. Oil color on paper. 109 x 98 cm (42.9 x 38.6 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Eom Yu Jeong, Tokyo series, 2016. Gouache on paper. 56 x 42 cm (22 x 16.5 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Eom Yu Jeong, Tokyo series, 2016. Gouache on paper. 56 x 42 cm (22 x 16.5 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

Indeed, your fascination with the human body is a recurring theme in your body of work, spanning from earlier series like Relationship (2012) and Body (2012-14) to your recent exhibition Night Waves (2021) at Hakgojae Design Gallery. While there are distinct appearances of human figures in your Iceland series (2014), figures in the majority of your works tend to be characterized more by their gestures and bodily shapes rather than by recognizable facial features.

That is true. As evident in Relationship (2012), I have been consistently exploring the depiction of human relationships. I've maintained an archive of bodily expressions for an extended period, aiming to capture the subtle nuances of physical gestures. Through years of drawing human bodies, I've come to appreciate how nuanced gestures, such as the way one rests their chin on their hand, tilts their shoulder, or the direction in which their feet point, often reveal more about a person than their eyes, nose, or mouth. With this perspective in mind, I believe the face naturally assumes a relatively minor role compared to the significance of hands and feet in my work. My exploration of human drawings remains an ongoing endeavor, and each time I engage with this subject matter, I observe how these subtle details continually evolve.

![Installation view of Night Waves at Hakgojae Design, PROJECT SPACE, 2021. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Eom Yu Jeong, Night Face, 2021. Gouache on paper. 32 x 24 cm (12.6 x 9.45 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of Night Waves at Hakgojae Design, PROJECT SPACE, 2021. Courtesy of the artist]()

So, when you bring an object or figure onto the canvas or paper, is it fair to say that you lean more towards interpreting their body language rather than relying solely on objective observation?

That's a question I've been grappling with myself. I would say it's more accurate to describe my approach as initially expressing my visual experiences through drawing and painting, rather than imposing a clear theme on the work. When I'm faced with plants, nature, or inanimate objects, my observations tend to be primarily objective, focusing on their external appearances. However, when it comes to human figures, I make an effort to focus on my inner emotions during our encounters. It's as if I borrow the human body as a means to express those experiential elements. Given that these works heavily depend on personal intuition, I hope viewers approach them with a broad perspective rather than trying to define them with specific keywords or making assumptions about the circumstances surrounding them.

As you briefly mentioned, your subjects can be categorized into nature, objects, and human figures. Do you prefer to work on a series for each of these subjects?

No, not exactly. I consistently and regularly document what I see and experience, and I believe that this ongoing process naturally leads to the development of my work over time. While my work can be visually divided into the categories you mentioned, I treat them all with equal significance, and one subject often serves as an inspiration for the next work featuring a different subject. They exist in an organic relationship with each other.

For instance, after spending time working on human figures, that experience might inspire me to seek out rock as my next subject, and conversely, when I focus on drawing rocks for an extended period, I start to view human figures as if they were rocks. In the act of drawing, they begin to resemble each other in surprising ways.

![Installation view of White Mountain at Artist Run Space 413, 2014. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of White Mountain at Artist Run Space 413, 2014. Courtesy of the artist]()

You navigate various artistic mediums, including drawing, painting, and video. How do you determine which medium to use for a particular project?

My choice of medium often depends on the essence of what I want to convey. When I aim to express something with depth, like a melting mountain or a natural landscape, I tend to lean towards painting. When I wish to emphasize the linear or structural aspects of elements, such as plants, drawing becomes my preferred medium. I would say that the subject matter drives my choice of medium, rather than the medium dictating the subject.

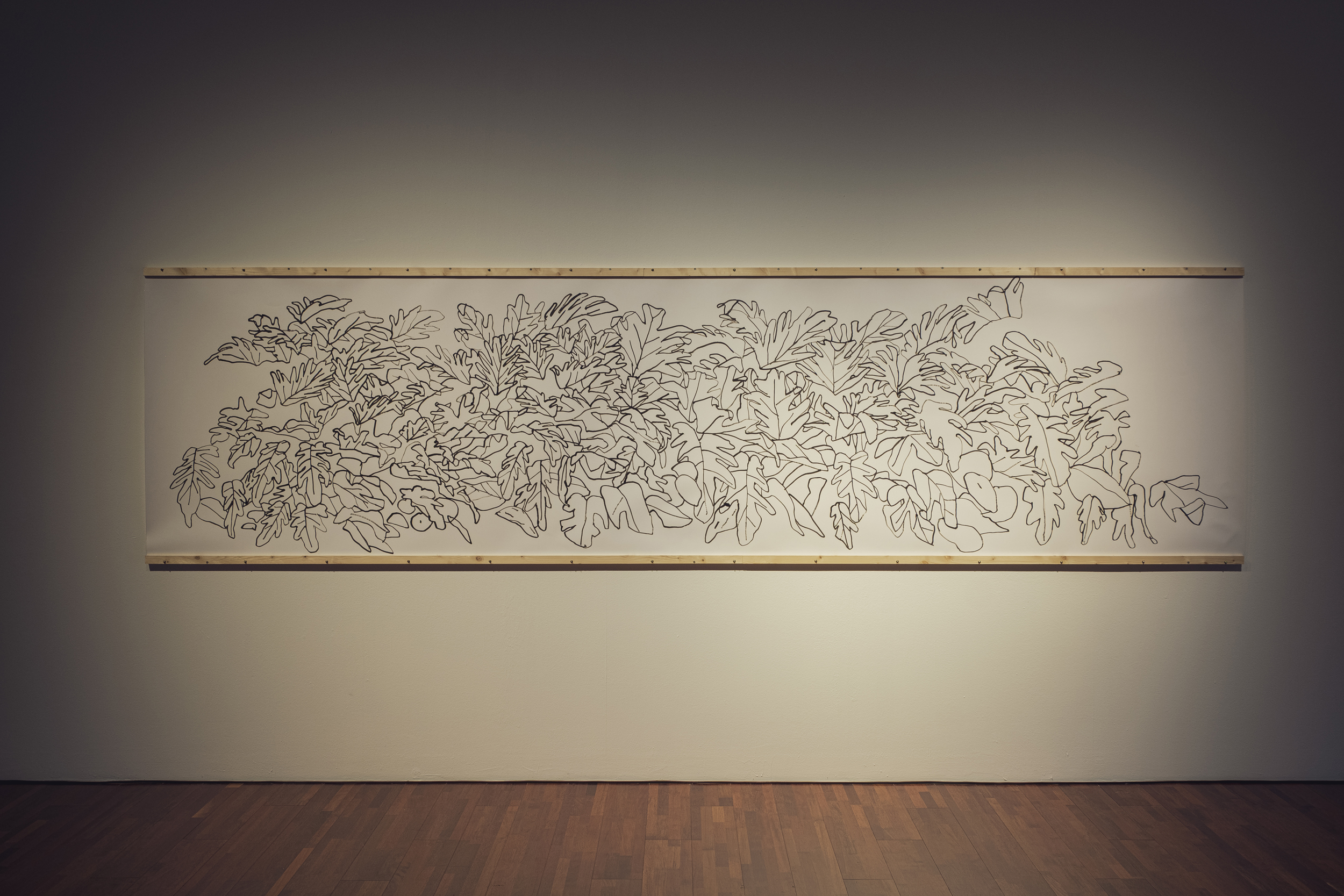

![Installation view of Feuilles at SOSHO, 2021. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of Feuilles at SOSHO, 2021. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of Araucaria at Cheongju Art Studio, 2019. Courtesy of the artist]()

I can't help but mention the prestigious Golden Letter prize you received in 2021 for the Best Book Design from All Over the World. Could you please share more about the series Feuilles (2019-21), which earned you this award?

Feuilles is the culmination of three years' worth of work. It represents a record of my observations made in various locations and time periods. You may as well compare it to a study of the various facets of a plant. Due to this award, some might view me as a "plant artist" (chuckles), but my interest lies less in becoming a botanical expert and more in my curiosity about the intricate, multi-layered structures and lines found in plants. Additionally, it provided me with an opportunity to break away from conventional drawing methods, allowing me to explore plants as an unfamiliar subject matter for a fresh perspective.

![Installation view of Study for Selem at Kim Hee Soo Art Center Art Gallery, 2021. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of Study for Selem at Kim Hee Soo Art Center Art Gallery, 2021. Courtesy of the artist]()

When you mention "observation," does that involve studying a subject in one place for an extended period, as you did with works like White Mountain (2014) or Glacier (2018)?

For the Hand-tied Flowers series (2021) or Study for Selem (2021), yes. I made an effort to observe a single subject from various angles over a set period of time. This approach started during the pandemic when I had limited opportunities to go out, prompting me to purchase cut flowers. Interestingly, this approach also influenced my way into creating animations like Tunnel (2014). The act of repeatedly drawing not only echoes the characteristics of animation but also piqued my curiosity about comparing the concept of time encapsulated on a flat surface to that of moving film. While a still painting possesses its own sense of time, it undergoes a transformation into a distinct, moving form when the images accumulate into a continuous sequence. It becomes a captured moment in an illusion, as if in different rhythmic waves of time.

![Eom Yu Jeong, Glenn Gould series, 2014. Oil color on paper. 42 x 56 cm (16.5 x 22 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

Your interest in time is well reflected in Glenn Gould (2014), a series of paintings that also inspired an animation based on a video featuring the pianist playing J.S. Bach's composition. In this work, you divided Gould's motion into nineteen distinct paintings, eventually transforming them into an animated video. Could you explain more about the concept of time within the realm of painting?

For me, time in painting embodies a sense of fluidity. It's fundamentally about the process. When I embark on creating a new piece of work, it requires a significant investment of time and patience, involving countless rounds of revisions. Every time I return to my work, even after a day I've convinced myself it's complete, it presents itself in an entirely new light. It somehow always appears before me in a completely different way than it did the day before. Witnessing this, I've come to realize that the notion of perfection or completion is boundless, much like a star in the universe. I may have thought I failed to complete my work on a particular day, but, in a sense, that's simply another version of what we call ‘completion.’ Much like life itself, it's an ever-evolving process.

![Eom Yu Jeong, Bush, 2023. Gouache and acrylic on canvas. 194 x 337 cm (76.4 x 132.7 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

During Frieze Seoul week, you simultaneously hosted a solo exhibition titled Three Shapes at A-Lounge Gallery and participated in a two-person show called Blue Face and Black Peony at Space Willing N Dealing. Could you provide a brief overview of your new works featured in these exhibitions?

In my latest solo show, I'll be unveiling new works featuring snow, bushes, and rocks. These subjects had been on my mind for 2-3 years when my previous works focused on plants garnered attention. I wanted to explore deeper into the concept of the plane, an interest that was reignited during my residency in Iceland back in 2014. If Araucaria (2019) exhibited distinctive linear features and revolved around the rhythms inherent in their structure, these new works explore the treatment of multiple subjects simultaneously. Instead of presenting them in recognizable forms, my intention was to simplify and emphasize the format itself, which naturally resulted in a blurred identity for each subject. Looking back, it might appear more intricate than some of my previous works.

Eom Yu Jeong's solo exhibition, Three Shapes, is currently on display at A-Lounge Gallery until Sep 16, 2023. The group exhibit, Blue Face and Black Peony, at Space Willing N Dealing will be open until Sep 17, 2023.

For further details, please visit:

A-Lounge Gallery: http://a-lounge.kr/

Space Willing N Dealing: https://www.willingndealing.org/

Have you always had the aspiration to become a painter?

I’ve always had a deep desire to become a painter since I was very young, too young to even remember when it began. During my undergrad years, however, my school didn't particularly support drawing as a medium, which occasionally left me frustrated. Then, during my period as an exchange student at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in Baltimore, I experienced a lot of pivotal changes. During my time there, I discovered, for the first time, that even small-sized drawings could be regarded as artworks. With the guidance of a supportive professor and engaging with lectures that differed from conventional painting classes, my perspective began to expand.

Upon returning to Korea, I delved into courses that focused on the human body. This marked the inception of my ongoing project as well as the compilation of a drawing archive featuring human gestures and bodies. It has since served as the fundamental foundation for the artwork I create today.

Swipe to see more images

Indeed, your fascination with the human body is a recurring theme in your body of work, spanning from earlier series like Relationship (2012) and Body (2012-14) to your recent exhibition Night Waves (2021) at Hakgojae Design Gallery. While there are distinct appearances of human figures in your Iceland series (2014), figures in the majority of your works tend to be characterized more by their gestures and bodily shapes rather than by recognizable facial features.

That is true. As evident in Relationship (2012), I have been consistently exploring the depiction of human relationships. I've maintained an archive of bodily expressions for an extended period, aiming to capture the subtle nuances of physical gestures. Through years of drawing human bodies, I've come to appreciate how nuanced gestures, such as the way one rests their chin on their hand, tilts their shoulder, or the direction in which their feet point, often reveal more about a person than their eyes, nose, or mouth. With this perspective in mind, I believe the face naturally assumes a relatively minor role compared to the significance of hands and feet in my work. My exploration of human drawings remains an ongoing endeavor, and each time I engage with this subject matter, I observe how these subtle details continually evolve.

Swipe to see more images

So, when you bring an object or figure onto the canvas or paper, is it fair to say that you lean more towards interpreting their body language rather than relying solely on objective observation?

That's a question I've been grappling with myself. I would say it's more accurate to describe my approach as initially expressing my visual experiences through drawing and painting, rather than imposing a clear theme on the work. When I'm faced with plants, nature, or inanimate objects, my observations tend to be primarily objective, focusing on their external appearances. However, when it comes to human figures, I make an effort to focus on my inner emotions during our encounters. It's as if I borrow the human body as a means to express those experiential elements. Given that these works heavily depend on personal intuition, I hope viewers approach them with a broad perspective rather than trying to define them with specific keywords or making assumptions about the circumstances surrounding them.

As you briefly mentioned, your subjects can be categorized into nature, objects, and human figures. Do you prefer to work on a series for each of these subjects?

No, not exactly. I consistently and regularly document what I see and experience, and I believe that this ongoing process naturally leads to the development of my work over time. While my work can be visually divided into the categories you mentioned, I treat them all with equal significance, and one subject often serves as an inspiration for the next work featuring a different subject. They exist in an organic relationship with each other.

For instance, after spending time working on human figures, that experience might inspire me to seek out rock as my next subject, and conversely, when I focus on drawing rocks for an extended period, I start to view human figures as if they were rocks. In the act of drawing, they begin to resemble each other in surprising ways.

Swipe to see more images

You navigate various artistic mediums, including drawing, painting, and video. How do you determine which medium to use for a particular project?

My choice of medium often depends on the essence of what I want to convey. When I aim to express something with depth, like a melting mountain or a natural landscape, I tend to lean towards painting. When I wish to emphasize the linear or structural aspects of elements, such as plants, drawing becomes my preferred medium. I would say that the subject matter drives my choice of medium, rather than the medium dictating the subject.

Swipe to see more images

I can't help but mention the prestigious Golden Letter prize you received in 2021 for the Best Book Design from All Over the World. Could you please share more about the series Feuilles (2019-21), which earned you this award?

Feuilles is the culmination of three years' worth of work. It represents a record of my observations made in various locations and time periods. You may as well compare it to a study of the various facets of a plant. Due to this award, some might view me as a "plant artist" (chuckles), but my interest lies less in becoming a botanical expert and more in my curiosity about the intricate, multi-layered structures and lines found in plants. Additionally, it provided me with an opportunity to break away from conventional drawing methods, allowing me to explore plants as an unfamiliar subject matter for a fresh perspective.

Swipe to see more images

When you mention "observation," does that involve studying a subject in one place for an extended period, as you did with works like White Mountain (2014) or Glacier (2018)?

For the Hand-tied Flowers series (2021) or Study for Selem (2021), yes. I made an effort to observe a single subject from various angles over a set period of time. This approach started during the pandemic when I had limited opportunities to go out, prompting me to purchase cut flowers. Interestingly, this approach also influenced my way into creating animations like Tunnel (2014). The act of repeatedly drawing not only echoes the characteristics of animation but also piqued my curiosity about comparing the concept of time encapsulated on a flat surface to that of moving film. While a still painting possesses its own sense of time, it undergoes a transformation into a distinct, moving form when the images accumulate into a continuous sequence. It becomes a captured moment in an illusion, as if in different rhythmic waves of time.

Your interest in time is well reflected in Glenn Gould (2014), a series of paintings that also inspired an animation based on a video featuring the pianist playing J.S. Bach's composition. In this work, you divided Gould's motion into nineteen distinct paintings, eventually transforming them into an animated video. Could you explain more about the concept of time within the realm of painting?

For me, time in painting embodies a sense of fluidity. It's fundamentally about the process. When I embark on creating a new piece of work, it requires a significant investment of time and patience, involving countless rounds of revisions. Every time I return to my work, even after a day I've convinced myself it's complete, it presents itself in an entirely new light. It somehow always appears before me in a completely different way than it did the day before. Witnessing this, I've come to realize that the notion of perfection or completion is boundless, much like a star in the universe. I may have thought I failed to complete my work on a particular day, but, in a sense, that's simply another version of what we call ‘completion.’ Much like life itself, it's an ever-evolving process.

During Frieze Seoul week, you simultaneously hosted a solo exhibition titled Three Shapes at A-Lounge Gallery and participated in a two-person show called Blue Face and Black Peony at Space Willing N Dealing. Could you provide a brief overview of your new works featured in these exhibitions?

In my latest solo show, I'll be unveiling new works featuring snow, bushes, and rocks. These subjects had been on my mind for 2-3 years when my previous works focused on plants garnered attention. I wanted to explore deeper into the concept of the plane, an interest that was reignited during my residency in Iceland back in 2014. If Araucaria (2019) exhibited distinctive linear features and revolved around the rhythms inherent in their structure, these new works explore the treatment of multiple subjects simultaneously. Instead of presenting them in recognizable forms, my intention was to simplify and emphasize the format itself, which naturally resulted in a blurred identity for each subject. Looking back, it might appear more intricate than some of my previous works.

Eom Yu Jeong's solo exhibition, Three Shapes, is currently on display at A-Lounge Gallery until Sep 16, 2023. The group exhibit, Blue Face and Black Peony, at Space Willing N Dealing will be open until Sep 17, 2023.

For further details, please visit:

A-Lounge Gallery: http://a-lounge.kr/

Space Willing N Dealing: https://www.willingndealing.org/

© 2023 Radar