Hong Lee Hyun Sook (b. 1958)

“Near the Willow Tree”

EN/KO

Released on 14 Sep 2023

Featured in ep. 1

︎︎

Just moments before the scheduled interview, HONG LEE HYUN SOOK connected with Radar via FaceTime. On her screen, a picturesque scene

of willow trees stretching across Hangang Park appeared. Since her debut

exhibit Mourning Undone in 1988, Hong Lee has led her journey as an

artist with notable exhibitions including Menopause Ceremony (Emu

Artspace, 2012) and Swoosh, Tsu-pu (ARKO Art Center, 2021). Lately, her

delight has been the serene beauty of the park where her studio is located. Over

the past few decades, her work has been actively interpreted and analyzed in

the context of eco-feminism and feminism, challenging the patriarchal norms

ingrained in our social structure. Consistently pushing the boundaries, her

works have guided viewers into uncharted territory for the past 35 years. In

this interview, Radar aimed to uncover her most recent interest.

Traversing installation, video, and performance, Hong Lee’s works have been featured in the 2nd Frieze Seoul Film (2023); the 14th Gwangju Biennale (2023); Bu-chun Art Bunker MMH hall(2021), Bu-chun; and ARKO Art Center, Seoul (2021).

![A photo of Nanjido Park near Hong Lee's studio, Sep 10, 2023. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A still from a video of Nanjido Park taken by the artist, 2023. Courtesy of the artist]()

What’s behind you over the screen?

Can you see the willow trees behind me? Aren’t they just stunning? They typically grow on the water's edge, serving as a bridge between the land and the water. Unfortunately, in the early 1980s, all of them were removed as part of an extensive government-led Han River development project, which aimed to reshape the river in preparation for the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Regrettably, as a consequence, the once-thriving willows were uprooted and replaced with cold concrete for a variety of unjustifiable reasons. Thanks to the restoration project, they are now experiencing a remarkable resurgence. Witnessing their return fills me with indescribable joy.

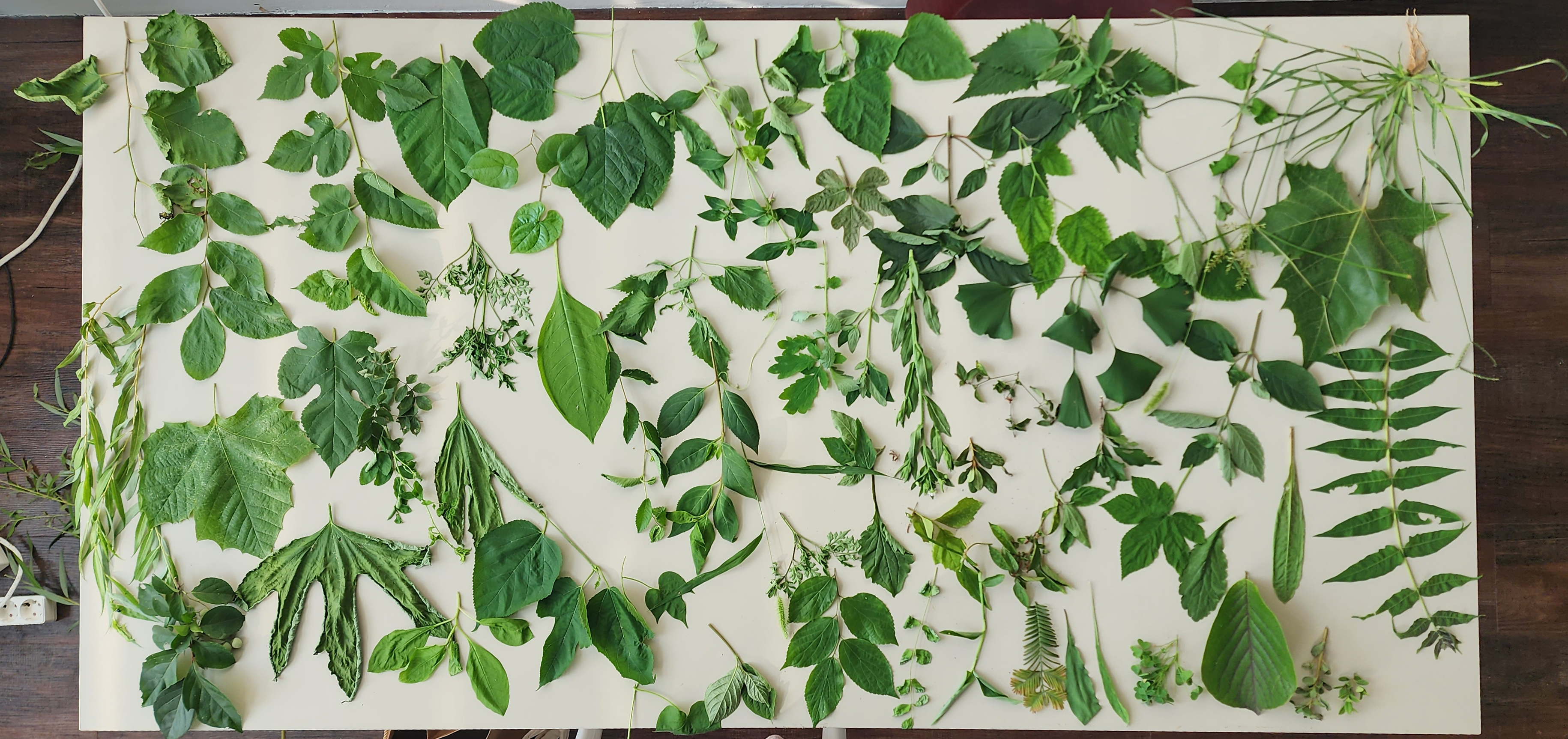

![A photo of plants collected by the artist, Aug 13, 2023. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A photo of the plants after a month, Sep 10, 2023. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A photo of SeMA Nanji Residency building. Courtesy of the artist.]()

![A photo of the artist's studio, 2023. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A photo of the climbing center next to SeMA Nanji Residency. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A view from the artist's studio, 2023. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A view from the artist's studio, 2023. Courtesy of the artist]()

You are currently a part of SeMA Nanji Residency. Has having a studio in Nanjido* Park given you any new experiences or inspiration?

Lately, I've developed a keen interest in observing plants that I've been collecting around my studio. Watching their gradual transformation each day has been truly captivating, as it reveals the intricate relationship between hydration and these plants. When they become dehydrated, it's as if they morph into entirely different entities. In my free time, I often hop on a bike to explore the beautiful scenery in the park. From time to time, I also try to listen to the whispers of the willow trees.

From my window, I have a clear view of an industrial complex that harnesses landfill gas for renewable energy production, along with a garbage incinerator. Recently, I've been frequently visiting another island called Eulsukdo in Busan, where I found it fascinating to observe the similarities and differences between these two islands. Compared to Nanjido, Eulsukdo has thinner willow trees, as it opened up its riverfront relatively later than Nanji. It’s been quite fun to compare and analyze their subtle distinctions.

Sometimes, I wonder if the willow trees on each island communicate with one another, perhaps through some form of telepathy. Looking back, I recall how disheartened I was by what happened in 1988 with all those trees. Yet, as I witness the resurgence of trees around the park, I've come to realize that, with the passage of time, I had simply pushed those emotions—the guilt and sadness I felt for the trees—aside and carried on with my own life, which now fills me with a sense of embarrassment. My profound empathy for nature, which I thought I had developed, turned out to be fleeting and momentary. There are so many things that we forget but shouldn't. In that sense, I believe we should consciously trace back our forgotten memories, expand our thoughts, and imagine beyond our usual boundaries, rather than solely relying on intuition.

*Located on the Han River, Nanjido served as Seoul's official dump site from 1978 to 1992. It has since transformed into an eco-friendly park.

It seems like the discovery of those willows in the park was an unexpected stroke of serendipity for you. To backtrack a bit, I understand that your undergraduate major was in sculpture. What prompted your transition to installation art?

During my college years, I found myself irresistibly drawn to the concept of art, Buddhism, and the mountains. These were passions I wanted to explore, having not had the opportunity to do so during my high school days. It eventually led me to immerse myself in the idea of Buddhism at a temple, where I would engage in rigorous practices like performing a 1080-times bow and occasionally enduring a 10-day fast and such. I spent several years doing mountain climbing as well.

In the realm of art, I found myself extremely happy in hands-on work with earth, sculpting and shaping clay into tangible forms. I think this natural affinity for working with physical materials eventually sparked my curiosity about the concept of space. This curiosity led me to pursue further studies in stage art at the National Theatre Graduate School. It was during this time that I was introduced to the relatively new concept of large-scale, spectacular installations from the West. Consequently, my focus gradually shifted towards the creation of immersive spaces, a departure from the world of crafting small-scale sculptures in many respects.

![Installation view of Mourning Undone at Il Gallery, Seoul, 1988. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of Mourning Undone at Il Gallery, Seoul, 1988. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A cover of the exhibition catalogue. Courtesy of the artist]()

The elements of earth, Buddhism, and mountains continue to play a prominent role in your recent works. In your inaugural solo exhibit, Mourning Undone, in 1988, didn't you incorporate a willow tree into the installation?

Yes, I did. That actually marks the first instance where I integrated willow trees into an exhibit. I wanted to commemorate the loss of those trees I had observed. At that time, I lived on a hill facing Bukhan Mountain. Rows of willows stood in front of my home, and I would often wave my hands at them as I passed by. Then, one spring day in 1988, out of the blue, I noticed that all the willows in my neighborhood had been cut down and lay scattered in the street. Shocked, I traced the whereabouts of these cut-down trees, as I wanted to include them in my show. To my surprise, I discovered they had been transferred to a toothpick factory in Incheon. When I contacted the factory, a young chairman offered to provide some of the trees in exchange for my help in designing a logo for their business. I vividly recall working on the design in a corner of the factory and then loading a batch of trees into my vehicle to return them to my place in Seoul. That was when the trees first found their way into my work.

For the exhibit, I created a pathway lined with these trees, inviting the audience to wander among them and ultimately find themselves inside this marked path. It was an immersive installation, a concept not commonly seen back in those days.

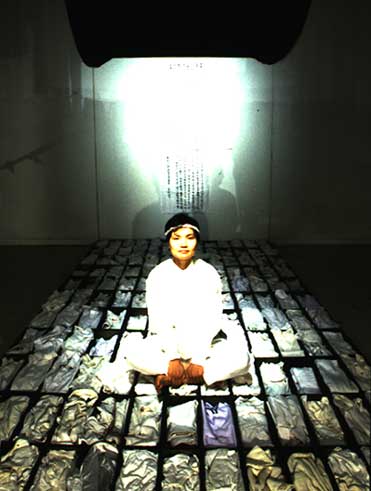

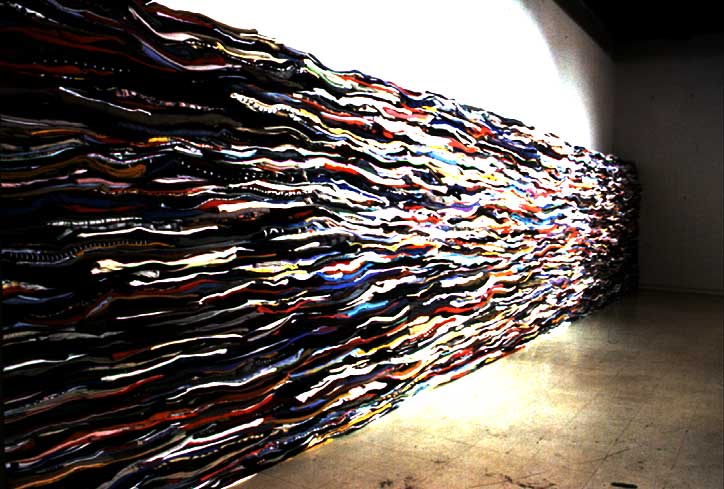

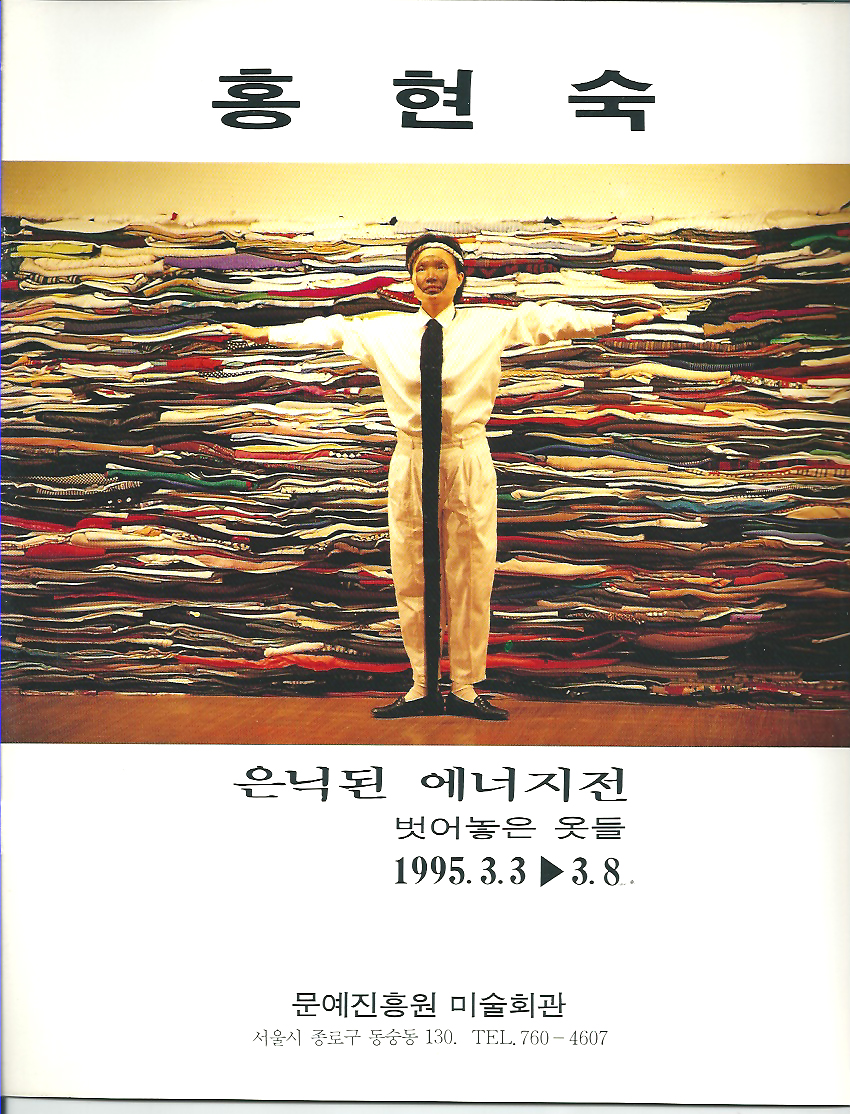

![Installation view of Concealed Energy at Misulhoegwan (now known as ARKO), Seoul, 1995. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A portrait of Hong Lee in Concealed Energy, 1995. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of Concealed Energy at Misulhoegwan (now known as ARKO), Seoul, 1995. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A cover of the exhibition catalogue. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of Hong Lee's public installation work at National Theatre, Seoul, 1997. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of Hong Lee's public installation work at National Theatre, Seoul, 1997. Courtesy of the artist]()

So, that marked the beginning of your large-scale installation work. In your subsequent solo exhibit, Concealed Energy (1995) at what was then Misulhoegwan, now known as ARKO, you presented an installation composed of clothing, which later became one of the recurring core materials in your works. It's also intriguing how starkly it contrasts with your previous material, trees, in terms of its characteristics.

Yes, that was the beginning of my use of clothing as a medium. It first started from a pile of clothes left behind by my father, who had recently passed away. My father passed away a week before he turned 60. That period also marked the transition of my name from Hong Hyun Sook to Hong Lee Hyun Sook. My father had spent his entire life in the clothing business, and he had a deep passion for dressing. When he left behind this substantial pile of clothes, I initially didn't know what to do with them, so I left them in the basement for a year. Then, at some point, I started contemplating how I could use them to pay tribute to him and eventually decided to create a ritual of my own. In one section of the museum venue, I neatly stacked up the clothes, and aside from them, I created multiple small coffin cases with white clothes enclosed, creating a pathway on the ground. It felt as though my dad was present at the end of that path. On the wall, I displayed a poem dedicated to him.

Unlike trees, as you pointed out, clothes possess the ability to adapt and transform depending on the context in which they are used. They reappeared in my installation in 1997 at the National Theatre, where I placed clothing between the staircases of the theater, which could be considered a form of Soft Sculpture.

Over time, I found myself more and more drawn to large-scale installation art—a medium that allowed the presentation of so-called ‘spectacle’ and ambitious creations. This interest is evident in my later works, such as the one in which I covered a 30-meter-long Odusan Unification Tower with bags of snacks in 2022.

![Installation view of Hong Lee's public installation work at Unification Observatory, 2000. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of Hong Lee's public installation work at Unification Observatory, 2000. Courtesy of the artist]()

Following your first solo show, you continued with public installations at venues such as the Seoul Arts Center (1997) and a pedestrian bridge at Insa-dong (2000). Then, for your eighth solo show, Grass and Fur (2005), you introduced video works for the first time, which garnered a lot of attention. What prompted this shift in materials?

It was an exhibit held at Alternative Space Pool. I created my own room within the venue and exhibited four videos, including Wings, Watering, and Gym. In terms of method, I brought my spectacle and grand-scale public installations back into a white cube. In terms of content, I started shedding light on personal, intimate elements. At that time, raising two boys who were only a year apart significantly constrained my physical and intellectual freedom. Whenever I attempted to focus on something unrelated to the kids, one of them would get hurt. I had to maintain a delicate balance between work and daily life. I yearned to move forward or explore new horizons, but my domestic responsibilities tied me down. This naturally led me to focus on personal narratives; my societal role as a middle-aged woman and mom, feelings of solitude, the sense of isolation that comes with raising a child, and the complexities of caregiving, commitment, and household chores of a woman.

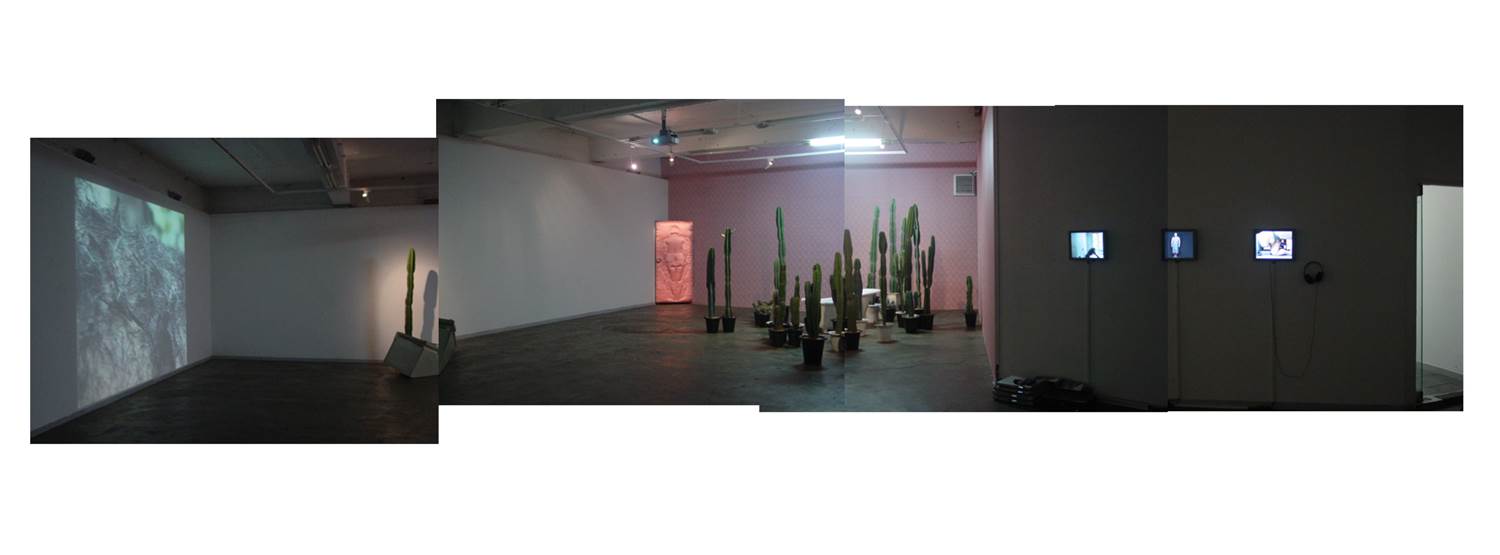

![Installation view of Glass and Fur at ArtSpace Pool, Seoul, 2005. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Hong Lee Hyun Sook, In the Neighborhood of Seokgwangsa-sa (still), 2020. Single channel. 15 min 47 sec. Courtesy of the artist]()

![Hong Lee Hyun Sook, In the Neighborhood of Seokgwangsa-sa (still), 2020. Single channel. 15 min 47 sec. Courtesy of the artist]()

Throughout your journey as an artist, your focus has evolved from large-scale public installations to works rooted in more personal experiences. Is this also reflected in the three films to be screened during Frieze Film Seoul?

The three works to be shown at Amado Art Space/Lab are Being a Lion (2017), Being a Whale (2018), and In the Neighborhood of Seokgwang-sa (2020). Through these films, I attempted to engage with non-human beings – a lion, a whale, and a stray cat. I sought to mimic their languages and gestures, which can be interpreted within the context of the need for imagination that I mentioned earlier in our conversation. I constantly imagine realms beyond our immediate perception, where the unknown resides. Art serves as one of the few means that allows us to transcend the confines of our current circumstances. I strive to view the world through a fresh lens, even if it may not always be comfortable or familiar. To perceive something in an unconventional way, you must consciously make an effort to become aware of the issues surrounding you. One can only address problems if one is able to perceive them.

In the end, however, I wasn’t able to attend the opening of the exhibition.

![A photo of the climbing center near the artist's studio, Sep 2023. Courtesy of the artist]()

![A photo of willow trees near the artist's studio, Sep 2023. Courtesy of the artist]()

Why couldn't you attend the opening?

Next to my studio, there's a climbing center currently getting ready to host the World Youth Climbing Competition. During my stay here, witnessing the preparations for the contest has been very exciting and intriguing. On the opening day, I unexpectedly had the chance to observe their preparatory work in progress during my commute to the studio.

Did you know that the placement of the rocks on the climbing wall isn't determined by meticulous, engineered calculations? Instead, climbers adjust them physically to suit their own body shapes through repeated falls, climbs, and countless trial-and-error attempts. There's a dedicated job for this called a 'route setter.' This also brought to mind my work, What You Touch Now (2019, 2022), which captures the climbing process of Wolchulsan Mountain and was presented at the 2023 Gwangju Biennale. I couldn't resist the urge to stay, observe, and capture this fascinating scene. That's why I couldn't attend. It has been a truly delightful experience to reconnect with willows and the world of climbing after all these years.

Hong Lee Hyun Sook’s three videos, Being a Lion (2017), Being a Whale (2018), and In the Neighborhood of Seokgwangsa (2020), were displayed during the 2nd Frieze Seoul Film (2023) at Amado Art Space/Lab. You can find further information on the following website: https://www.frieze.com/article/hong-lee-hyun-sook

Traversing installation, video, and performance, Hong Lee’s works have been featured in the 2nd Frieze Seoul Film (2023); the 14th Gwangju Biennale (2023); Bu-chun Art Bunker MMH hall(2021), Bu-chun; and ARKO Art Center, Seoul (2021).

Swipe to see more images

What’s behind you over the screen?

Can you see the willow trees behind me? Aren’t they just stunning? They typically grow on the water's edge, serving as a bridge between the land and the water. Unfortunately, in the early 1980s, all of them were removed as part of an extensive government-led Han River development project, which aimed to reshape the river in preparation for the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Regrettably, as a consequence, the once-thriving willows were uprooted and replaced with cold concrete for a variety of unjustifiable reasons. Thanks to the restoration project, they are now experiencing a remarkable resurgence. Witnessing their return fills me with indescribable joy.

Swipe to see more images

You are currently a part of SeMA Nanji Residency. Has having a studio in Nanjido* Park given you any new experiences or inspiration?

Lately, I've developed a keen interest in observing plants that I've been collecting around my studio. Watching their gradual transformation each day has been truly captivating, as it reveals the intricate relationship between hydration and these plants. When they become dehydrated, it's as if they morph into entirely different entities. In my free time, I often hop on a bike to explore the beautiful scenery in the park. From time to time, I also try to listen to the whispers of the willow trees.

From my window, I have a clear view of an industrial complex that harnesses landfill gas for renewable energy production, along with a garbage incinerator. Recently, I've been frequently visiting another island called Eulsukdo in Busan, where I found it fascinating to observe the similarities and differences between these two islands. Compared to Nanjido, Eulsukdo has thinner willow trees, as it opened up its riverfront relatively later than Nanji. It’s been quite fun to compare and analyze their subtle distinctions.

Sometimes, I wonder if the willow trees on each island communicate with one another, perhaps through some form of telepathy. Looking back, I recall how disheartened I was by what happened in 1988 with all those trees. Yet, as I witness the resurgence of trees around the park, I've come to realize that, with the passage of time, I had simply pushed those emotions—the guilt and sadness I felt for the trees—aside and carried on with my own life, which now fills me with a sense of embarrassment. My profound empathy for nature, which I thought I had developed, turned out to be fleeting and momentary. There are so many things that we forget but shouldn't. In that sense, I believe we should consciously trace back our forgotten memories, expand our thoughts, and imagine beyond our usual boundaries, rather than solely relying on intuition.

*Located on the Han River, Nanjido served as Seoul's official dump site from 1978 to 1992. It has since transformed into an eco-friendly park.

It seems like the discovery of those willows in the park was an unexpected stroke of serendipity for you. To backtrack a bit, I understand that your undergraduate major was in sculpture. What prompted your transition to installation art?

During my college years, I found myself irresistibly drawn to the concept of art, Buddhism, and the mountains. These were passions I wanted to explore, having not had the opportunity to do so during my high school days. It eventually led me to immerse myself in the idea of Buddhism at a temple, where I would engage in rigorous practices like performing a 1080-times bow and occasionally enduring a 10-day fast and such. I spent several years doing mountain climbing as well.

In the realm of art, I found myself extremely happy in hands-on work with earth, sculpting and shaping clay into tangible forms. I think this natural affinity for working with physical materials eventually sparked my curiosity about the concept of space. This curiosity led me to pursue further studies in stage art at the National Theatre Graduate School. It was during this time that I was introduced to the relatively new concept of large-scale, spectacular installations from the West. Consequently, my focus gradually shifted towards the creation of immersive spaces, a departure from the world of crafting small-scale sculptures in many respects.

Swipe to see more images

The elements of earth, Buddhism, and mountains continue to play a prominent role in your recent works. In your inaugural solo exhibit, Mourning Undone, in 1988, didn't you incorporate a willow tree into the installation?

Yes, I did. That actually marks the first instance where I integrated willow trees into an exhibit. I wanted to commemorate the loss of those trees I had observed. At that time, I lived on a hill facing Bukhan Mountain. Rows of willows stood in front of my home, and I would often wave my hands at them as I passed by. Then, one spring day in 1988, out of the blue, I noticed that all the willows in my neighborhood had been cut down and lay scattered in the street. Shocked, I traced the whereabouts of these cut-down trees, as I wanted to include them in my show. To my surprise, I discovered they had been transferred to a toothpick factory in Incheon. When I contacted the factory, a young chairman offered to provide some of the trees in exchange for my help in designing a logo for their business. I vividly recall working on the design in a corner of the factory and then loading a batch of trees into my vehicle to return them to my place in Seoul. That was when the trees first found their way into my work.

For the exhibit, I created a pathway lined with these trees, inviting the audience to wander among them and ultimately find themselves inside this marked path. It was an immersive installation, a concept not commonly seen back in those days.

Swipe to see more images

So, that marked the beginning of your large-scale installation work. In your subsequent solo exhibit, Concealed Energy (1995) at what was then Misulhoegwan, now known as ARKO, you presented an installation composed of clothing, which later became one of the recurring core materials in your works. It's also intriguing how starkly it contrasts with your previous material, trees, in terms of its characteristics.

Yes, that was the beginning of my use of clothing as a medium. It first started from a pile of clothes left behind by my father, who had recently passed away. My father passed away a week before he turned 60. That period also marked the transition of my name from Hong Hyun Sook to Hong Lee Hyun Sook. My father had spent his entire life in the clothing business, and he had a deep passion for dressing. When he left behind this substantial pile of clothes, I initially didn't know what to do with them, so I left them in the basement for a year. Then, at some point, I started contemplating how I could use them to pay tribute to him and eventually decided to create a ritual of my own. In one section of the museum venue, I neatly stacked up the clothes, and aside from them, I created multiple small coffin cases with white clothes enclosed, creating a pathway on the ground. It felt as though my dad was present at the end of that path. On the wall, I displayed a poem dedicated to him.

Unlike trees, as you pointed out, clothes possess the ability to adapt and transform depending on the context in which they are used. They reappeared in my installation in 1997 at the National Theatre, where I placed clothing between the staircases of the theater, which could be considered a form of Soft Sculpture.

Over time, I found myself more and more drawn to large-scale installation art—a medium that allowed the presentation of so-called ‘spectacle’ and ambitious creations. This interest is evident in my later works, such as the one in which I covered a 30-meter-long Odusan Unification Tower with bags of snacks in 2022.

Swipe to see more images

Following your first solo show, you continued with public installations at venues such as the Seoul Arts Center (1997) and a pedestrian bridge at Insa-dong (2000). Then, for your eighth solo show, Grass and Fur (2005), you introduced video works for the first time, which garnered a lot of attention. What prompted this shift in materials?

It was an exhibit held at Alternative Space Pool. I created my own room within the venue and exhibited four videos, including Wings, Watering, and Gym. In terms of method, I brought my spectacle and grand-scale public installations back into a white cube. In terms of content, I started shedding light on personal, intimate elements. At that time, raising two boys who were only a year apart significantly constrained my physical and intellectual freedom. Whenever I attempted to focus on something unrelated to the kids, one of them would get hurt. I had to maintain a delicate balance between work and daily life. I yearned to move forward or explore new horizons, but my domestic responsibilities tied me down. This naturally led me to focus on personal narratives; my societal role as a middle-aged woman and mom, feelings of solitude, the sense of isolation that comes with raising a child, and the complexities of caregiving, commitment, and household chores of a woman.

Swipe to see more images

Throughout your journey as an artist, your focus has evolved from large-scale public installations to works rooted in more personal experiences. Is this also reflected in the three films to be screened during Frieze Film Seoul?

The three works to be shown at Amado Art Space/Lab are Being a Lion (2017), Being a Whale (2018), and In the Neighborhood of Seokgwang-sa (2020). Through these films, I attempted to engage with non-human beings – a lion, a whale, and a stray cat. I sought to mimic their languages and gestures, which can be interpreted within the context of the need for imagination that I mentioned earlier in our conversation. I constantly imagine realms beyond our immediate perception, where the unknown resides. Art serves as one of the few means that allows us to transcend the confines of our current circumstances. I strive to view the world through a fresh lens, even if it may not always be comfortable or familiar. To perceive something in an unconventional way, you must consciously make an effort to become aware of the issues surrounding you. One can only address problems if one is able to perceive them.

In the end, however, I wasn’t able to attend the opening of the exhibition.

Swipe to see more images

Why couldn't you attend the opening?

Next to my studio, there's a climbing center currently getting ready to host the World Youth Climbing Competition. During my stay here, witnessing the preparations for the contest has been very exciting and intriguing. On the opening day, I unexpectedly had the chance to observe their preparatory work in progress during my commute to the studio.

Did you know that the placement of the rocks on the climbing wall isn't determined by meticulous, engineered calculations? Instead, climbers adjust them physically to suit their own body shapes through repeated falls, climbs, and countless trial-and-error attempts. There's a dedicated job for this called a 'route setter.' This also brought to mind my work, What You Touch Now (2019, 2022), which captures the climbing process of Wolchulsan Mountain and was presented at the 2023 Gwangju Biennale. I couldn't resist the urge to stay, observe, and capture this fascinating scene. That's why I couldn't attend. It has been a truly delightful experience to reconnect with willows and the world of climbing after all these years.

Hong Lee Hyun Sook’s three videos, Being a Lion (2017), Being a Whale (2018), and In the Neighborhood of Seokgwangsa (2020), were displayed during the 2nd Frieze Seoul Film (2023) at Amado Art Space/Lab. You can find further information on the following website: https://www.frieze.com/article/hong-lee-hyun-sook

© 2023 Radar