At the core of Jesse Chun’s works lies her approach and methodology of "unlanguaging," a way of deconstructing the fixed state of language that has accumulated over layers of time, culture, and sociopolitical structures. Spanning across video, installation, and performance, Chun’s works are a nod to the world that has always existed but remained unseen, ready to be perceived and expressed through ideas that transcend reason and logic. Skillfully blending her critical perspectives on the politics and translations of language with the syntax of visual art, she expands the viewer’s world by blurring the limits of their language.

Recently, she showcased her first solo survey in Korea by participating in the 12th Seoul MediaCity Biennale. Her works have been featured at KADIST, San Francisco (2023); Whitechapel Gallery, London (2023); Ballroom Marfa, Texas (2023); Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2022); and Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, Toronto (2021). Chun is mainly based in New York.

![Installation view of 시: concrete poem(left) and O dust(right), 2023, at the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Seoul Museum of History, 2023. Courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art and the artist]()

![Installation view, from left:score for unlanguaging (천지문 and cosmos); And verse (혼잣말의 언어 그리고 cosmos) II; 술래 SULLAE, 2023, at the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Seoul Museum of History, 2023. Courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art and the artist]()

![Installation view of score for unlanguaging (천지문 and cosmos) at the Seoul Museum of Art for the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Seoul Museum of History, 2023. Courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art and artist]()

Congratulations on your debut solo survey at the 12th Seoul MediaCity Biennale. How has the experience been for you?

Thank you. It has been a wild journey for me. Prior to this, I hadn’t been back in Korea for 6 years. This is also the first time that I got to spend nearly 6 months in Seoul to make work here. The experience has had a profound impact on me. I’m planning on relocating to Korea for a while to continue the work. It’s been wonderful to physically have access to all the things I’ve always wanted to do, like engaging further with ancestral research, Korean folk literature traditions, and so on. It's also allowed me to delve into the writings left behind by my late grandmother and learn Korean shamanic paper cutting from a local Mudang (Shaman)—experiences that would have been impossible if I had remained physically distant.

As a survey, how much of this exhibition covers your oeuvre? Does it trace back to your very early works?

This survey mainly showcases my work from 2020 onward, as my work has undergone a significant transformation over the past three years. A substantial part of this transformation is deeply rooted in a spiritual awakening and philosophical negotiations or inquiries that I went through in the last few years. One of the profound influences on this is my late grandmother. She was a Korean folk dancer whose existence remained largely undocumented, even in family records. Later in life, she became a Buddhist monk and lived at a temple until her passing. It wasn't until after her passing in 2017 that I began to feel a genuine connection with her and understand her spiritual and philosophical pursuits. She communicated with me through dreams and transmissions. That connection has allowed me to deeply understand the non-linearity of time, narrative, and space. In the same way, for the survey, instead of tracing my work in a linear timeline, we focused more on the works that show the core of my practice and where it will continue to go.

Have your underlying artistic values shifted significantly compared to your earlier works?

No, while the visual and spiritual inquiries have evolved, the core of my work remains the same. It still asks the same questions about language—trying to unfix language itself from its entanglement with power, (colonial) ideologies, and its own sociocultural structures to see what other layers remain. Lately, I am more interested in language’s abilities to transcend the boundaries of physical borders, human ideologies, and time. I think my work has grown in a way where it is now thinking further into the possibilities of language, not only in a tangible sense but in a cosmic way.

Over the years, my works’ engagement with poetics has gotten deeper as I find that poetics are a very important, generative space. I have been engaging further with personal histories and my mutations in Korean folk literature to dig deeper into that. I think about various textures of language and try to decenter the "official" and “historic” narratives with various modes of (un)languaging, mutations, mistranslations, and utterances to the self. My work now fully delves into mapping language and its various cosmologies.

From my perspective, one significant factor contributing to the effective conveyance of your message seems to be your unique insider perspective in both cultures, rather than straddling the boundaries of each culture and merely incorporating cultural elements to create a traditional or 'exotic' layer.

My formative years in Korea left a lasting and powerful impact on me, allowing me the privilege to reinterpret traditional elements—Korean folk literature, for example—without resorting to exoticization (for the white gaze). I constantly question myself about the depth of my reinterpretation. The processes of mutation and translation play a pivotal role in my work. I am also interested in the untranslatable space. It’s interesting to see how my work is perceived in both the Western and now Korean contexts. Recently, I've come to realize that being a diasporic artist doesn’t mean that I have to choose one side; I can embrace and embody both contexts. That’s also why I want to spend more time in Seoul from now on; I want to fully connect with that part of myself and find that circularity within.

![Jesse Chun, 시: concrete poem, 2023. Graphite, hand cut Hanji (Korean mulberry paper), wood frame. 158.75 × 91.44 × 6.35 cm (62.5 x 36 x 2.5 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![(detail)]()

![Installation view, from left: 시: concrete poem, 2023 and 시: sea, 2022, at the Seoul Museum of Art for the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Seoul Museum of History, 2023. Courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art and the artist]()

![Installation view of 시: concrete poem, 2023, at the Seoul Museum of Art for the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Seoul Museum of History, 2023. Courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art and the artist]()

Could you elaborate a bit more about the works featured in the biennale?

As you step into the exhibition space, you'll encounter a series of my latest works, including 시: concrete poem (2023) and 시: Sea (2022), a freestanding video sculpture. 시: concrete poem (2023) is a series of large-scale sculptural drawings made of my reinterpretation of Korean paper cutting. In a meditative, time-based process, I draw hundreds of lines on the hanji using a pencil and then carefully cut out my anemic writing. I wanted to visualize the untranslatable space that comes from meditating on the diasporic conditions of language. I chose papercutting to question what it means to enunciate through shadows, gaps, silence, and time. Traditionally, Mudang would cut paper during Gut* and use it as a portal to summon spirits, ultimately burning it as part of the ritual. I liked that this tradition activated paper cutting as a portal to communicate with another world. It opens up the possibilities of language.

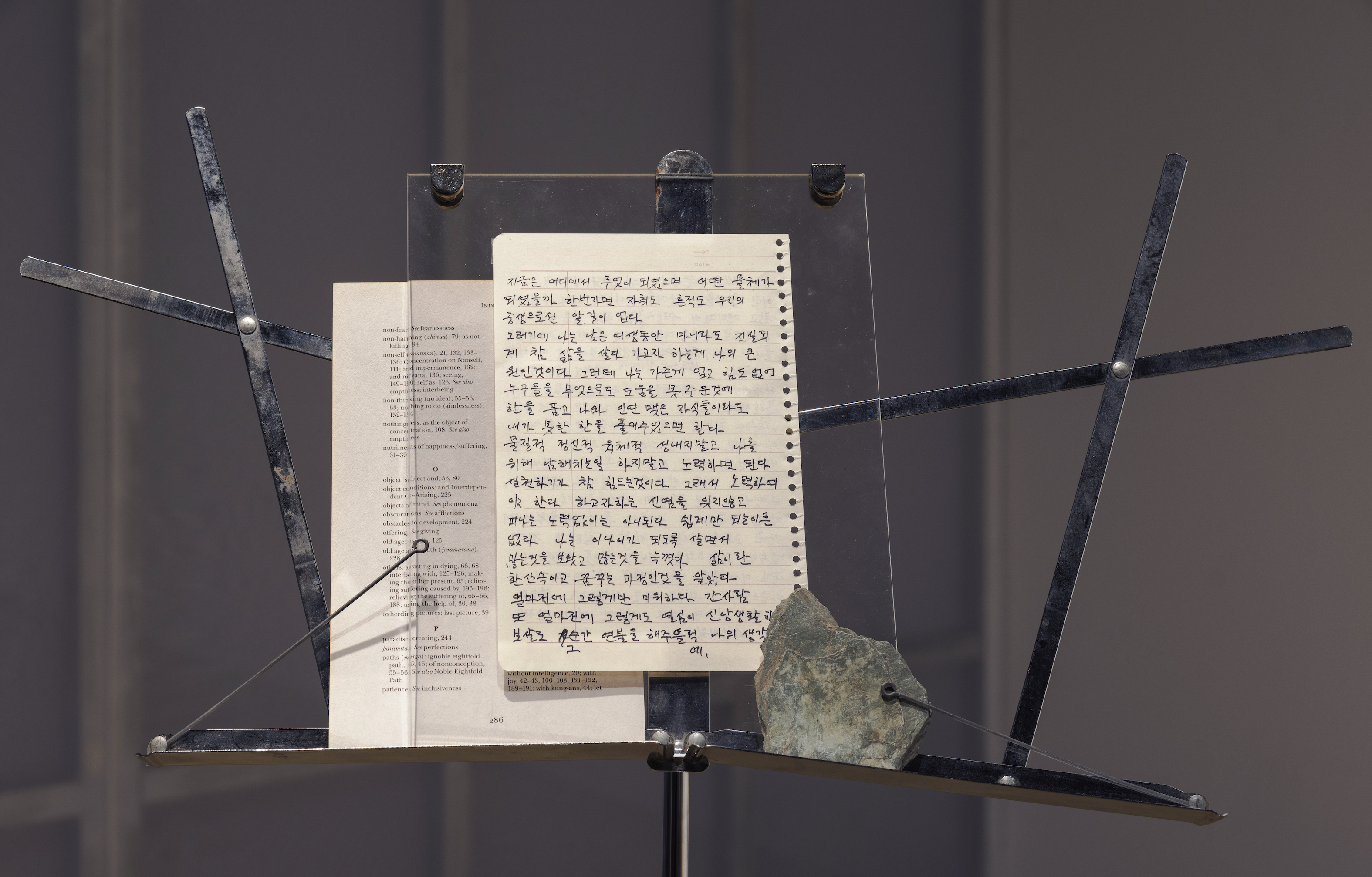

The exhibition also features my most recent short film, titled O dust (2023), and features 술래 SULLAE (2020), as well as a floor video piece titled And verse (혼잣말의 언어 그리고 cosmos). Additionally, it features a series of scores for unlanguaging, as well as new sculptural assemblages featuring my grandmother’s writings to me, along with my responses—to speak together across time and place.

*Gut refers to the rites performed by Korean shamans.

![Jesse Chun, O dust, 2023. 3 channel video installation, 3 mirrors. 7 min 6 sec video, with sound. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art and the artist]()

In your overall body of work, I frequently encounter elements of fluidity, both in terms of content and installation. Whether it's the flowing surface of water in pieces like O dust (2023) and 시: Sea (2022), the movement of clouds in O (for various skies) (2021), the dance portrayed in 술래 SULLAE (2020), or the use of mirrors in tongues of fire (2022–23), these elements naturally bring to mind the concept of fluidity in language, much like your description of language as "a shift to an ongoing, open-ended production of meaning." Do these installation elements primarily serve the purpose of embodying the concept of fluidity?

Absolutely. The installation is of great significance to me, just as much as the artwork itself. For this show, the biennale team and I have constructed four walls, including a large transparent wall crafted from Hanbok fabric, serving as an opaque and transparent pathway to connect both my video works, 술래 SULLAE and O dust. It was important for me to visually materialize the opacity, subtleties, and textures of language. I wanted the exhibition to flow together as a whole, like walking through an immersive poem. I wanted the exhibition to have that fluidity, circularity, and a flow of qi (기) energy as viewers walk through the exhibit.

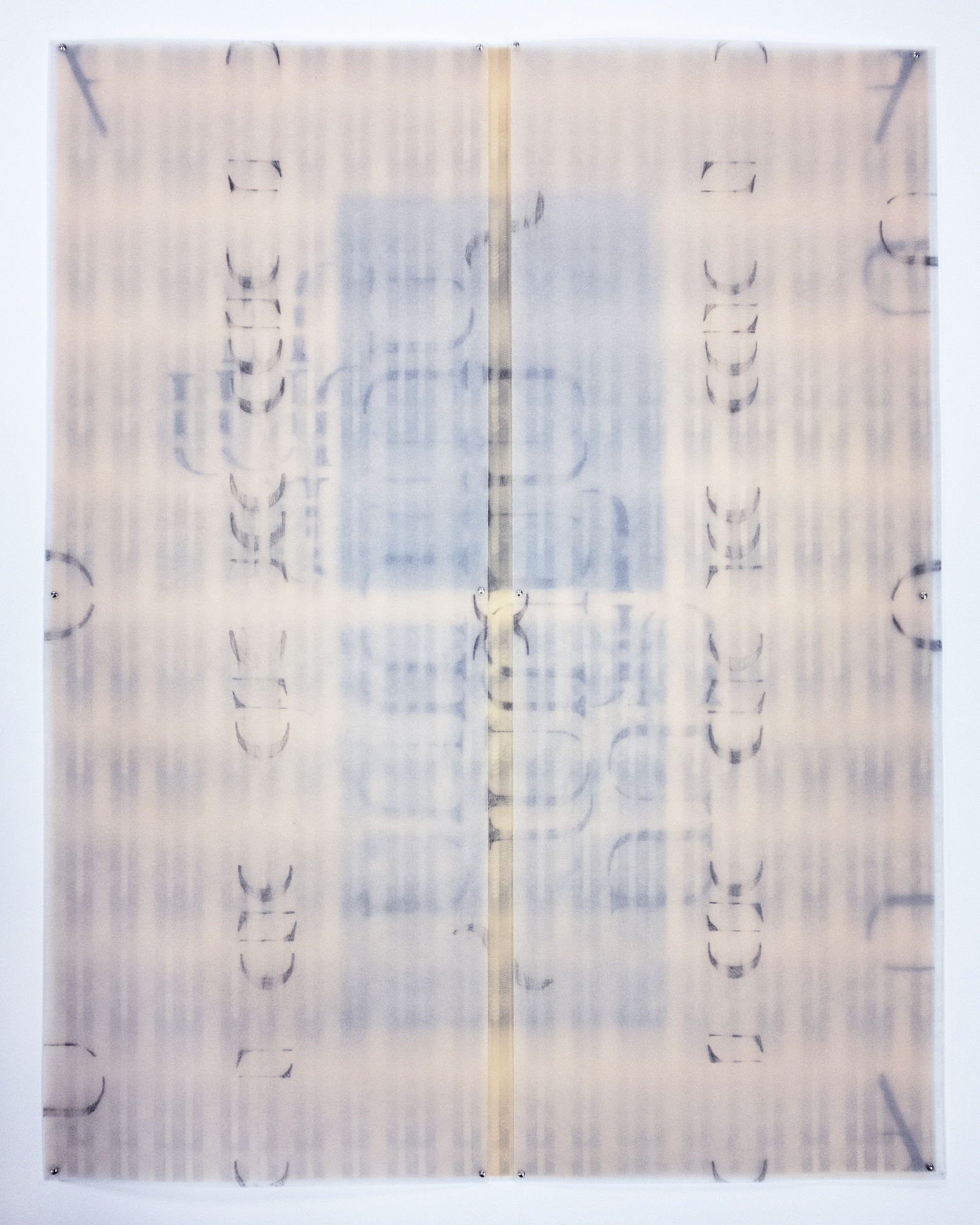

![Jesse Chun, score for unlanguaging. no082721, 2021. Graphite, pigment, vellum paper, pins. 27.9 x 21. 6 cm (11 x 8.5 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Installation view of score for unlanguaging at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, 2021. Courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art, Toronto, and the artist]()

I'm also intrigued by your series score for unlanguaging (2021–ongoing), both in terms of its medium and the installation. From what I know, they come to life through performances and collaborations with other artists. Given their lack of a visually universal notation, I’m curious to know how they are interpreted and activated. Could you provide more insight into this work?

Over the years, drawing has carried a larger significance for me. To me, both video and drawings are forms of written expression manifested in distinct visual mediums. They both serve the purpose of transforming visuals into poetics. score for unlanguaging is a series of sculptural drawings—layered, folded, pinned—that fragment and abstract the global lingua franca, English, into new abstractions. Using a Roman Alphabet (English) stencil, I don’t make English but instead map new cosmologies of language. Taking the world’s most dominant language as a site of departure, the abstract scores consider non-linear passages of language and meaning.

The scores do get activated through performances and collaborations with other artists from various fields. I invite them to “translate” and activate the score however they want. I can't predict how the performance will unfold until the very day it takes place. My dear friend and artist Li(sa) E. Harris performed the first iteration, and the artist JJJJJerome Ellis will perform the next one, which I am excited about.

![Installation view of score for unlanguaging on billboards, Toronto, Canada, 2022. Courtesy of the artist]()

In the installation views, I notice the presence of graphite rubbings positioned between the scores, which, for me, seems to evoke a sense of rest in a way akin to a pause in a musical note.

That is a beautiful reading of it. In the scores, I repeat the process of drawing and erasing. I have been thinking a lot about visualizing erasure itself. The graphite rubbings on the wall are the same as the framed score, because I want to allude to the space between what is said and what is unsaid. Marking the invisible visible in a tactile way with graphite.

![Installation view of notes on new moons / oak / sun (new moons are often invisible to the naked eye; notes by my grandmother Lee Oak Sun -- buddhist name Jeong Gak Haeng; other notes on history; my offerings; on speaking together), at the Seoul Museum of Art for the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Seoul Museum of History, 2023. Courtesy of Seoul Museum of Art and the artist]()

![(detail)]()

I recall your description of your work And verse (혼잣말의 언어 그리고 cosmos) (2022), where you mentioned your exploration of the method of "unlanguaging" leads to a place where language feels safe and interior. This struck me as particularly interesting because it seems to allude to the dual nature of language—the power it wields, sometimes to a constraining extent, once it enters the public domain.

Language is an incredibly intricate and powerful thing. It can hold and release so much. I am still learning to revere it as its own entity—its own body, spirit, and more. The colonial forces behind linguistic imperialism, especially behind English as the world’s most common language, have wielded language in a weaponized way for so long. This is why "unlanguaging" holds significance for me—it's a process of undoing to find new pathways and possibilities. To move toward poetry.

Recently, she showcased her first solo survey in Korea by participating in the 12th Seoul MediaCity Biennale. Her works have been featured at KADIST, San Francisco (2023); Whitechapel Gallery, London (2023); Ballroom Marfa, Texas (2023); Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2022); and Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, Toronto (2021). Chun is mainly based in New York.

Swipe to see more images

Congratulations on your debut solo survey at the 12th Seoul MediaCity Biennale. How has the experience been for you?

Thank you. It has been a wild journey for me. Prior to this, I hadn’t been back in Korea for 6 years. This is also the first time that I got to spend nearly 6 months in Seoul to make work here. The experience has had a profound impact on me. I’m planning on relocating to Korea for a while to continue the work. It’s been wonderful to physically have access to all the things I’ve always wanted to do, like engaging further with ancestral research, Korean folk literature traditions, and so on. It's also allowed me to delve into the writings left behind by my late grandmother and learn Korean shamanic paper cutting from a local Mudang (Shaman)—experiences that would have been impossible if I had remained physically distant.

As a survey, how much of this exhibition covers your oeuvre? Does it trace back to your very early works?

This survey mainly showcases my work from 2020 onward, as my work has undergone a significant transformation over the past three years. A substantial part of this transformation is deeply rooted in a spiritual awakening and philosophical negotiations or inquiries that I went through in the last few years. One of the profound influences on this is my late grandmother. She was a Korean folk dancer whose existence remained largely undocumented, even in family records. Later in life, she became a Buddhist monk and lived at a temple until her passing. It wasn't until after her passing in 2017 that I began to feel a genuine connection with her and understand her spiritual and philosophical pursuits. She communicated with me through dreams and transmissions. That connection has allowed me to deeply understand the non-linearity of time, narrative, and space. In the same way, for the survey, instead of tracing my work in a linear timeline, we focused more on the works that show the core of my practice and where it will continue to go.

Have your underlying artistic values shifted significantly compared to your earlier works?

No, while the visual and spiritual inquiries have evolved, the core of my work remains the same. It still asks the same questions about language—trying to unfix language itself from its entanglement with power, (colonial) ideologies, and its own sociocultural structures to see what other layers remain. Lately, I am more interested in language’s abilities to transcend the boundaries of physical borders, human ideologies, and time. I think my work has grown in a way where it is now thinking further into the possibilities of language, not only in a tangible sense but in a cosmic way.

Over the years, my works’ engagement with poetics has gotten deeper as I find that poetics are a very important, generative space. I have been engaging further with personal histories and my mutations in Korean folk literature to dig deeper into that. I think about various textures of language and try to decenter the "official" and “historic” narratives with various modes of (un)languaging, mutations, mistranslations, and utterances to the self. My work now fully delves into mapping language and its various cosmologies.

From my perspective, one significant factor contributing to the effective conveyance of your message seems to be your unique insider perspective in both cultures, rather than straddling the boundaries of each culture and merely incorporating cultural elements to create a traditional or 'exotic' layer.

My formative years in Korea left a lasting and powerful impact on me, allowing me the privilege to reinterpret traditional elements—Korean folk literature, for example—without resorting to exoticization (for the white gaze). I constantly question myself about the depth of my reinterpretation. The processes of mutation and translation play a pivotal role in my work. I am also interested in the untranslatable space. It’s interesting to see how my work is perceived in both the Western and now Korean contexts. Recently, I've come to realize that being a diasporic artist doesn’t mean that I have to choose one side; I can embrace and embody both contexts. That’s also why I want to spend more time in Seoul from now on; I want to fully connect with that part of myself and find that circularity within.

Swipe to see more images

Could you elaborate a bit more about the works featured in the biennale?

As you step into the exhibition space, you'll encounter a series of my latest works, including 시: concrete poem (2023) and 시: Sea (2022), a freestanding video sculpture. 시: concrete poem (2023) is a series of large-scale sculptural drawings made of my reinterpretation of Korean paper cutting. In a meditative, time-based process, I draw hundreds of lines on the hanji using a pencil and then carefully cut out my anemic writing. I wanted to visualize the untranslatable space that comes from meditating on the diasporic conditions of language. I chose papercutting to question what it means to enunciate through shadows, gaps, silence, and time. Traditionally, Mudang would cut paper during Gut* and use it as a portal to summon spirits, ultimately burning it as part of the ritual. I liked that this tradition activated paper cutting as a portal to communicate with another world. It opens up the possibilities of language.

The exhibition also features my most recent short film, titled O dust (2023), and features 술래 SULLAE (2020), as well as a floor video piece titled And verse (혼잣말의 언어 그리고 cosmos). Additionally, it features a series of scores for unlanguaging, as well as new sculptural assemblages featuring my grandmother’s writings to me, along with my responses—to speak together across time and place.

*Gut refers to the rites performed by Korean shamans.

In your overall body of work, I frequently encounter elements of fluidity, both in terms of content and installation. Whether it's the flowing surface of water in pieces like O dust (2023) and 시: Sea (2022), the movement of clouds in O (for various skies) (2021), the dance portrayed in 술래 SULLAE (2020), or the use of mirrors in tongues of fire (2022–23), these elements naturally bring to mind the concept of fluidity in language, much like your description of language as "a shift to an ongoing, open-ended production of meaning." Do these installation elements primarily serve the purpose of embodying the concept of fluidity?

Absolutely. The installation is of great significance to me, just as much as the artwork itself. For this show, the biennale team and I have constructed four walls, including a large transparent wall crafted from Hanbok fabric, serving as an opaque and transparent pathway to connect both my video works, 술래 SULLAE and O dust. It was important for me to visually materialize the opacity, subtleties, and textures of language. I wanted the exhibition to flow together as a whole, like walking through an immersive poem. I wanted the exhibition to have that fluidity, circularity, and a flow of qi (기) energy as viewers walk through the exhibit.

Swipe to see more images

I'm also intrigued by your series score for unlanguaging (2021–ongoing), both in terms of its medium and the installation. From what I know, they come to life through performances and collaborations with other artists. Given their lack of a visually universal notation, I’m curious to know how they are interpreted and activated. Could you provide more insight into this work?

Over the years, drawing has carried a larger significance for me. To me, both video and drawings are forms of written expression manifested in distinct visual mediums. They both serve the purpose of transforming visuals into poetics. score for unlanguaging is a series of sculptural drawings—layered, folded, pinned—that fragment and abstract the global lingua franca, English, into new abstractions. Using a Roman Alphabet (English) stencil, I don’t make English but instead map new cosmologies of language. Taking the world’s most dominant language as a site of departure, the abstract scores consider non-linear passages of language and meaning.

The scores do get activated through performances and collaborations with other artists from various fields. I invite them to “translate” and activate the score however they want. I can't predict how the performance will unfold until the very day it takes place. My dear friend and artist Li(sa) E. Harris performed the first iteration, and the artist JJJJJerome Ellis will perform the next one, which I am excited about.

In the installation views, I notice the presence of graphite rubbings positioned between the scores, which, for me, seems to evoke a sense of rest in a way akin to a pause in a musical note.

That is a beautiful reading of it. In the scores, I repeat the process of drawing and erasing. I have been thinking a lot about visualizing erasure itself. The graphite rubbings on the wall are the same as the framed score, because I want to allude to the space between what is said and what is unsaid. Marking the invisible visible in a tactile way with graphite.

Swipe to see more images

I recall your description of your work And verse (혼잣말의 언어 그리고 cosmos) (2022), where you mentioned your exploration of the method of "unlanguaging" leads to a place where language feels safe and interior. This struck me as particularly interesting because it seems to allude to the dual nature of language—the power it wields, sometimes to a constraining extent, once it enters the public domain.

Language is an incredibly intricate and powerful thing. It can hold and release so much. I am still learning to revere it as its own entity—its own body, spirit, and more. The colonial forces behind linguistic imperialism, especially behind English as the world’s most common language, have wielded language in a weaponized way for so long. This is why "unlanguaging" holds significance for me—it's a process of undoing to find new pathways and possibilities. To move toward poetry.

© 2023 Radar