Setting the stage before the curtain rises, waiting endlessly in airport queues, or immersing oneself in working. These are universal experiences,

encountered directly or indirectly, that resonate with us all. Easily

recognizable in their essence, they are incremental

steps toward a larger outcome, be it a concert, departure, or a completed

project

—

the subtle, often overlooked pillars that quietly support

moments of recognition and acclaim. JINA PARK assumes the role of an observer of these moments. She imparts a sense of permanence to these fleeting

instances unfolding before our eyes and visualizes the passage of

time. From

her

Lomography series in the early 2000s to recent

works, Radar

had a conversation with Park about her distinct perspective on the

often overlooked

intricacies of daily life.

Her works have been featured in prestigious institutions and galleries in both Korea and abroad, including the Busan Museum of Art (2023); Cheongju Museum of Art (2021); Kukje Gallery (2021); Hapjungjigu (2018); Plan.d (2015), Dusseldorf; and Doosan Gallery (2013), New York. They could be found in permanent collections of the Seoul Museum of Art, Daegu Art Museum, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s Art Bank, and Kumho Museum of Art. Park is based in Germany and Korea.

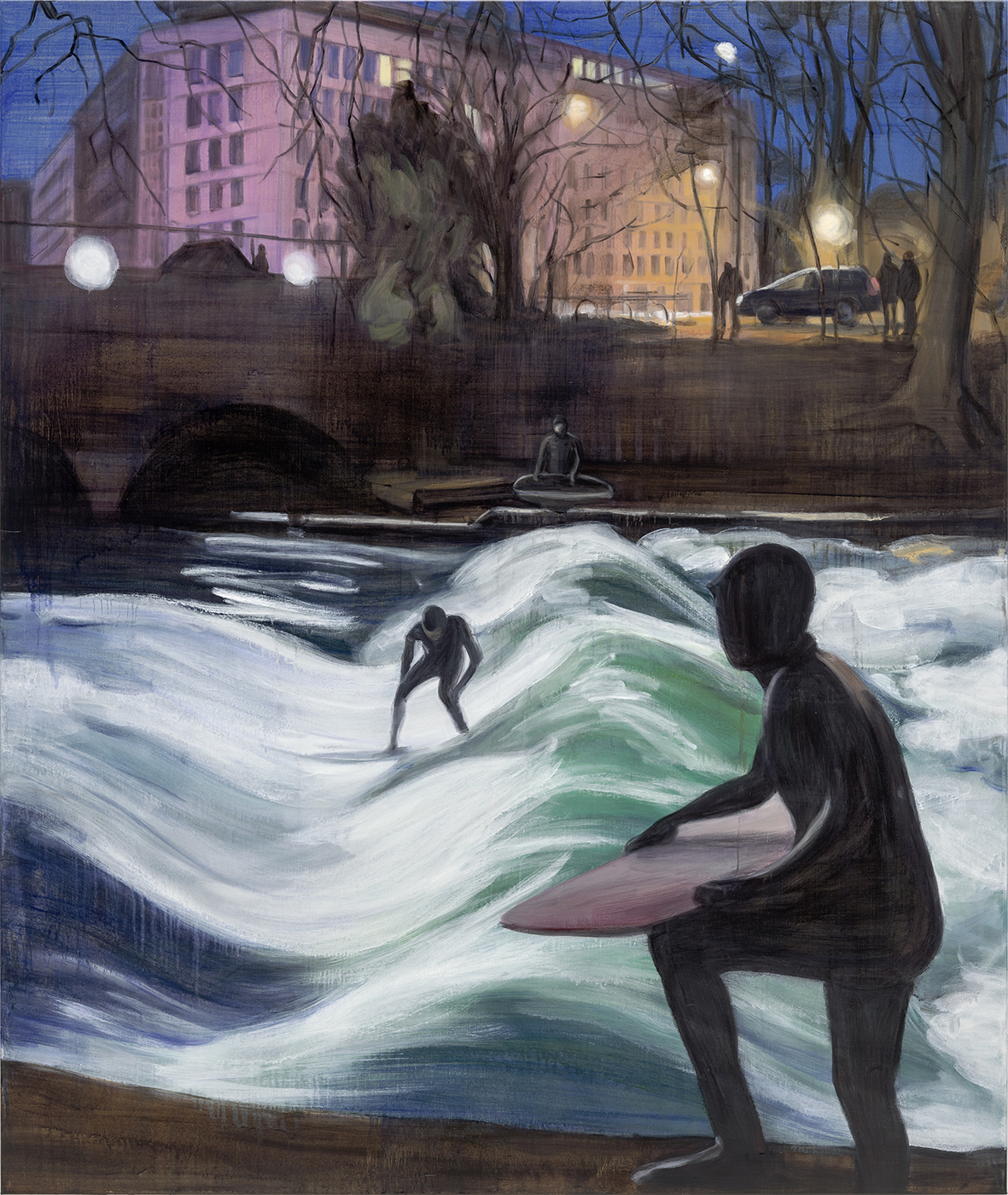

![Jina Park, Urban Surfer 11, 2022. Oil on linen. 154 x 130 cm (60.6 x 51.2 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

Where are you currently staying?

I'm in Nuremberg, Germany, at the moment. I usually travel between Seoul and here once or twice a year, spending about two to three months in Nuremberg. I wish I could stay here a bit longer, but most of my work is in Seoul, so it's not as easy as it sounds.

I’m sure Seoul and Nuremberg are quite different. Do you feel that difference directly influences your work?

Personally, I prefer Nuremberg for working, as the city is generally quiet and slow. Here, I’m relatively anonymous, and there’s no constant rush to be somewhere. The studio also offers more space to work. However, there are some minor inconveniences in my daily routine, like delays in obtaining necessary materials. The fact that I don’t own a car here or speak fluent German does not help. Compared to Seoul, things here require more time and cover greater distances, so to speak. Still, returning from the bustling streets of Seoul feels like a refreshing break.

You frequently use snapshots you've taken as the basis for your work. It seems like your artworks often start with observing people's lives through these images. Does the different atmosphere between the two cities also affect what you observe?

Certainly. I may not consciously perceive the direct impact, but the shift in environment makes me view my surroundings in unfamiliar ways. Just like when you return to Korea after traveling abroad for a while—suddenly, you start noticing little things that you used to overlook, you know.

![Jina Park, Crown, 2000. Acrylic on linen. 76 x 60 cm (30 x 23.7 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Jina Park, Flower, 2000. Acrylic on linen. 51 x 70 cm (20.1 x 27.6 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Jina Park, Radio heads, 2000. Acrylic on linen. 68 x 60 cm (26.8 x 23.7 in) each (diptych). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Jina Park, Love from London, 2002. Acrylic on linen. 80.5 x 100 cm (31.7 x 39.4 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

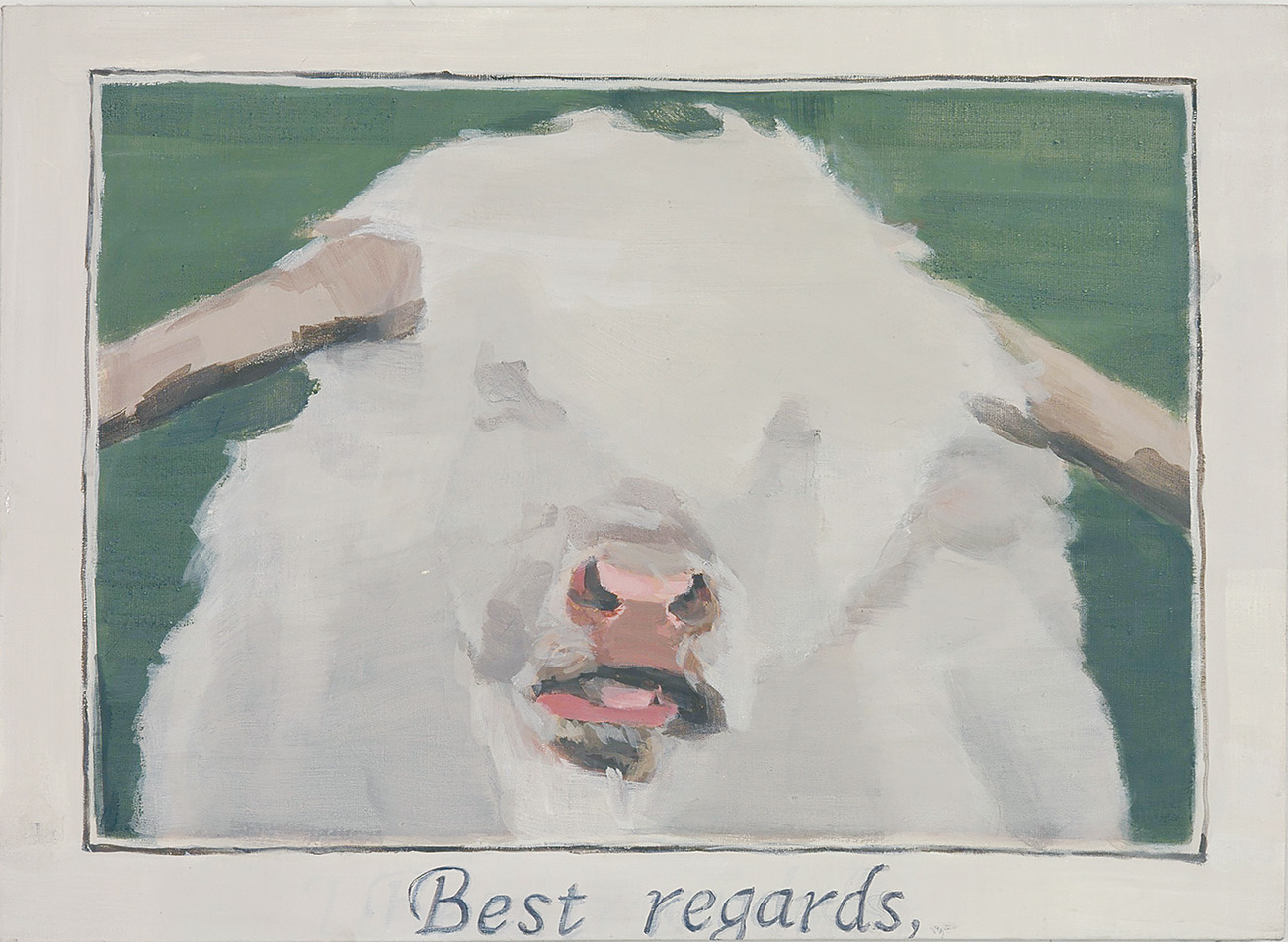

![Jina Park, Best Regards, 2002. Acrylic on linen. 74 x 100 cm (29 x 39.4 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

As I carefully browsed through your earlier works from the early to mid-2000s, I noticed that the emphasis on temporality, which is now quite prevalent in your recent works, was not as noticeable. By 'earlier works,' I am referring to pieces such as the Passport Photo (2000), Head (2000), or Postcard (2002) series.

Those works were created right after I graduated from graduate school. You may have noticed already, but at that time, I was deeply impressed by this one exhibition featuring the Belgian artist Luc Tuymans. His detailed expression of photographic characteristics through a painterly approach opened up vast possibilities in painting for me. It was from then on that I began working on pieces that captured brief narratives through snapshots or postcards of my surroundings.

![Jina Park, Garden, 2005. Oil on canvas. 109 x 145 cm (43 x 57.1 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Jina Park, Island, 2006. Oil on canvas. 135 x 194 cm (53.1 x 76.4 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

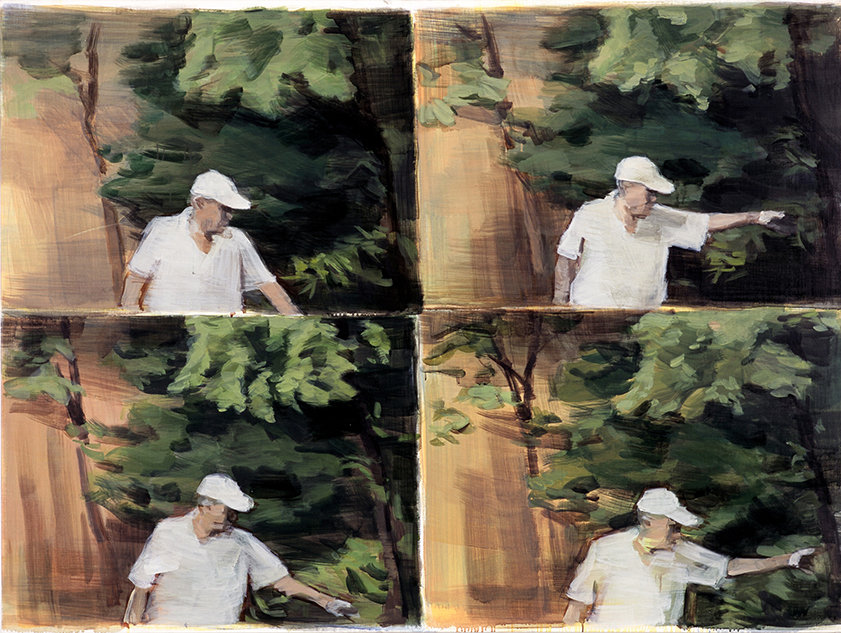

Another thing I noticed from works created during that time period is the four-panel composition, which I find very interesting. It seems like the beginning of your interest in the passage of time.

I personally refer to those series as the Lomography series. While it's not so common these days, there were many cheap toy cameras back then, costing around 30-40 bucks. They were simple cameras with just basic shooting functions, allowing you to roughly capture your subject. I started taking snapshots with those cameras, and I found their format quite interesting. Snapshots inherently have a casual feeling of being accidentally captured. Since they differ from precise framing and capturing, I wanted to actively utilize the characteristics of low-tech. It seemed to align well with my approach and sensibility towards painting at that time. Those cameras take four shots in one second, meaning four shots appear on one frame. So that’s when the format started to appear on my canvas.

That camera has four lenses, so it takes four shots in one second. In other words, four shots come out in one frame. I think that was when continuous shots began to emerge in my works. I don't think I was intentionally doing it; instead, I was experimenting out of interest, fascinated by the freshness of the moment and form. One might as well call it an interest in how that specific camera captured time. Looking back, I realized that many elements forming the basis of my current work had already begun with that Lomography series

Sometimes photography serves as a means of documenting the moment for archival purposes, capturing personal moments. When you capture images with your camera, what is your intention behind the lens?

To be honest, I’m not entirely sure. I guess I have both intentions. But in the past, I tended to lean more towards capturing subjective moments, viewing it as a relatively personal medium.

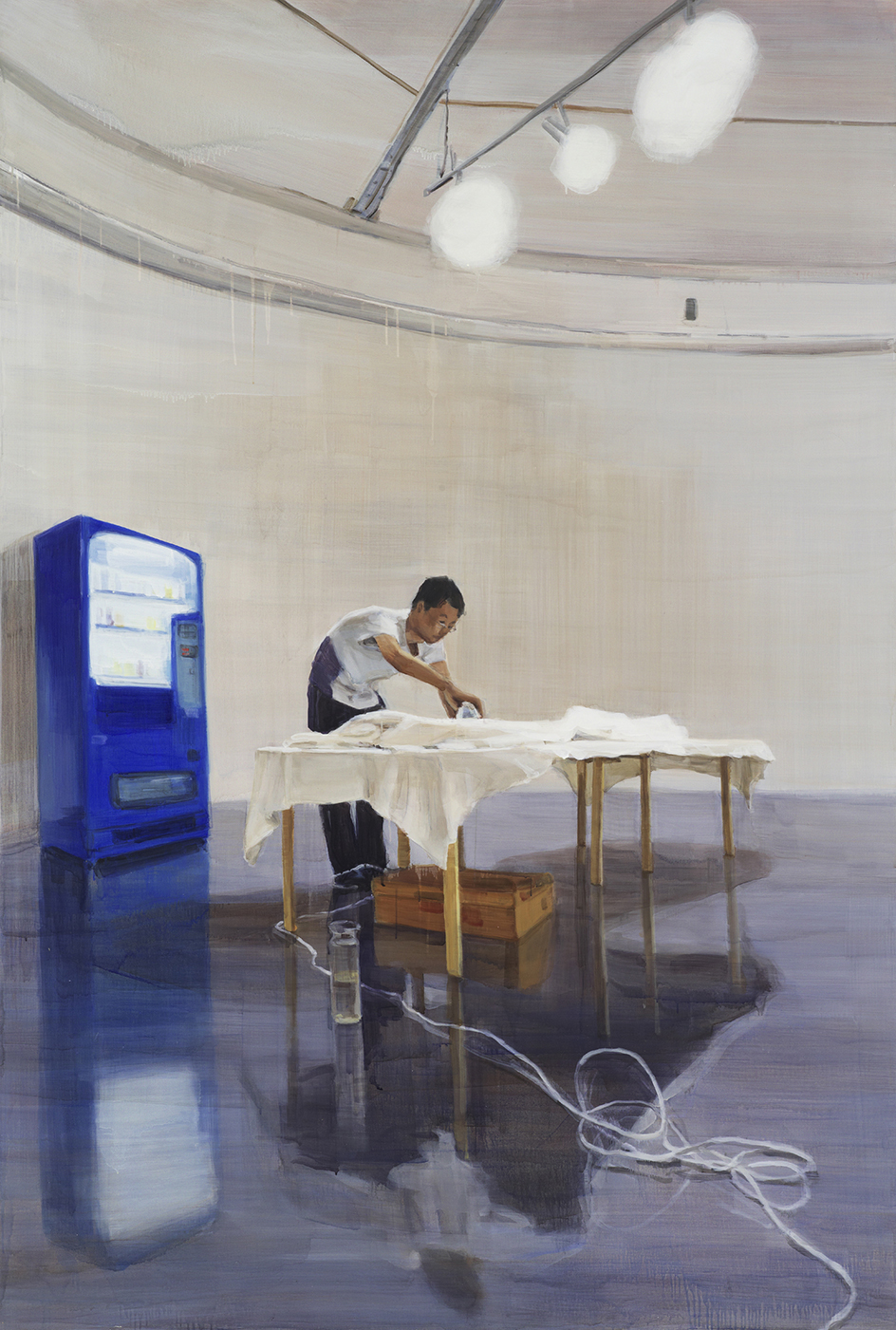

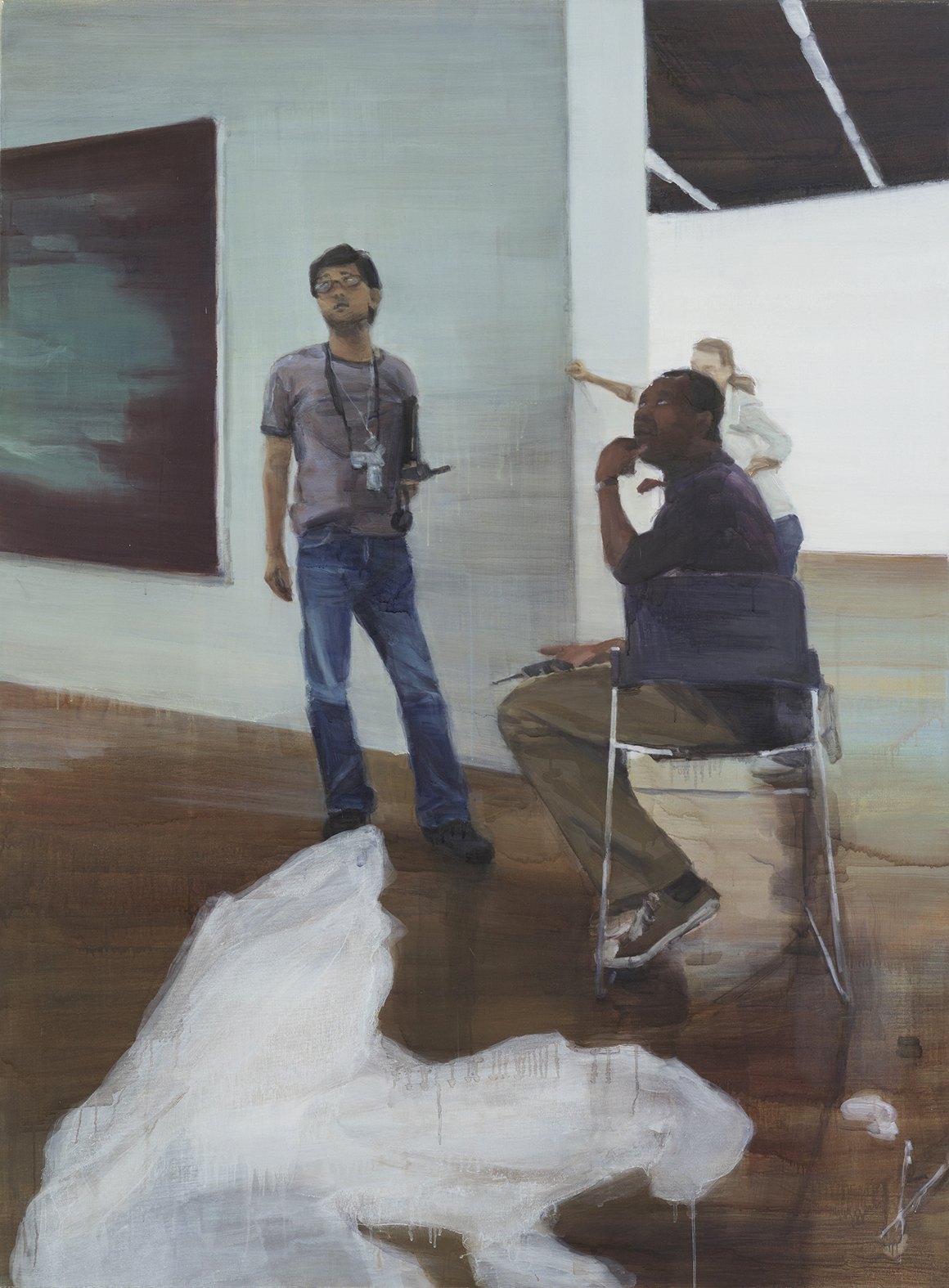

![Jina Park, A Man Ironing in a Round Gallery, 2010. Oil on canvas. 230 x 178 cm (90.6 x 70.1 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Jina Park, Lighting Above, 2009. Oil on canvas. 181.5 x 134 cm (71.5 x 52.8 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Jina Park, Two Stories, 2011. Oil on canvas. 235 x 190 cm (92.5 x 74.8 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

What makes you feel that way?

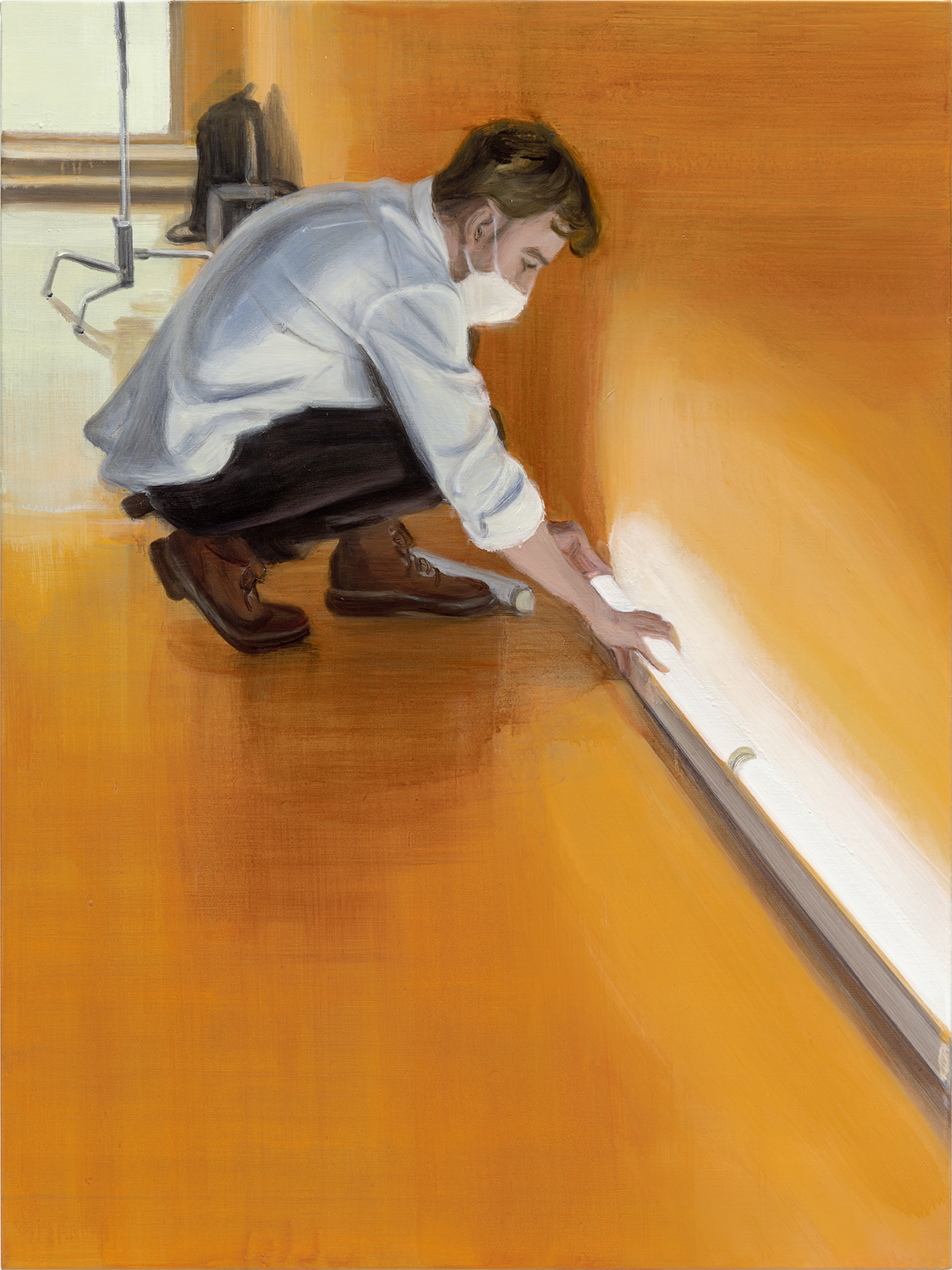

In the past, I often drew inspiration from my surroundings and frequently depicted scenes involving my acquaintances. However, around 2010, I began creating works that delved deeper into the depiction of exhibition spaces, such as A Man Ironing in a Round Gallery (2010) or Lighting Above (2009-2010), which blend the intention of capturing personal memory with documentation. For instance, I started photographing scenes observed at venues where I presented my works, which naturally led me to record the activities of people working on-site.

Since then, my works have become more documentary in nature, and I began more and more depicting strangers, those who I didn’t know well. Of course, this doesn't mean that my recent works lack personal significance. Occasionally, my friends still make appearances, and since most of the images are based on photos I took myself, they still represent intimate moments I've experienced. However, as I assume the role of an observer who doesn't actively intervene, they appear relatively more documentary.

From those photos you’ve taken, how do you select images to transfer onto the canvas?

I primarily focus on the actions of the figures. It's somewhat challenging to put into words, but the more I observe, the more I notice certain specific movements that draw my attention. They're nothing extraordinary, just the ordinary physical gestures we perform daily, like lifting objects while working or turning our heads to look at something—movements in a fleeting moment with a hint of tension. I narrow down the images based on these movements and sort of amalgamate them. Occasionally, when get lucky, everything aligns seamlessly, and the images from the photos can be directly transposed onto the canvas. However, most of the time, the desired composition needs to be crafted. In such cases, I choose the movements I like from various photos and arrange them on a single canvas.

![Jina Park, Making of Exhibitions, 2023. House paint, acrylic on wall and oil on linen. 450 x 850 cm (14.8 x 27.9 ft), 450 x 1130 cm (14.8 x 37 ft). Photo: Hahyung Kwon. Courtesy of the artist and Busan Museum of Art]()

![Jina Park, Installation view of Making of Exhibitions, 2023. Photo: Hahyung Kwon. Courtesy of the artist and Busan Museum of Art]()

![Jina Park, Installation view of Making of Exhibitions, 2023. Photo: Hahyung Kwon. Courtesy of the artist and Busan Museum of Art]()

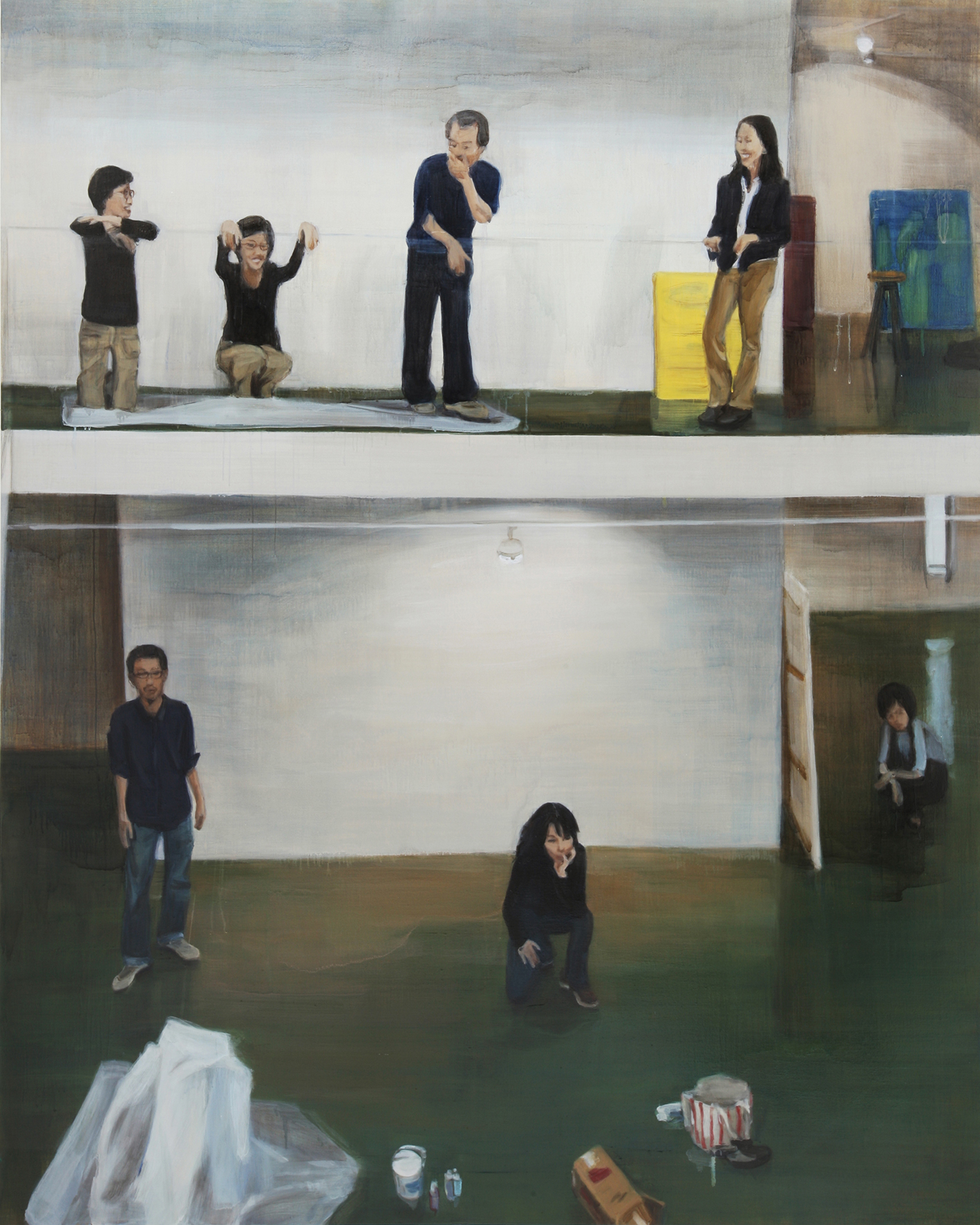

That makes me think of the continuity of images. I really enjoyed the work you showed at the Busan Museum of Art, Making of Exhibitions (2023). I loved how the images extend beyond the canvas, kind of acting as a conduit to the next sequence of action installation-wise. It also reminded me of your past exhibition Sometimes it sticks to my body held at Wess last year, in a way that it expanded the canvas into the entire space.

That commission I worked on at the Busan Museum of Art is one of my most recent works. It’s been a completely new venture for me, as I had never worked on a mural before. As you mentioned, in previous solo exhibitions like those at Wess, I had tried connecting the installation space with my drawings, imbuing an installation-like feature to a painting. At Wess, Hyejeong Chang, the curator, suggested the painting the walls with bold colors from the initial planning stage. For Making of Exhibitions, which was the museum’s final showcase before undergoing extensive renovations, the goal was to reflect on the museum's history as a space for art. So, from the outset, the curator wanted me to give me the freedom to uutilize the allocated exhibition space however I wished.

As I don't often get the opportunity to use such a large space, I decided to try something entirely new. About two months before the opening, I visited the space, diligently took photos, and tried to capture as many behind-the-scenes moments as possible. Using these photos as a starting point, I created two oil paintings and installed them in a way that extended beyond the canvas, integrating them into murals.

Were there any particularly memorable moments while you worked on the commission?

Given the constraints of nature of mural painting, you are only allowed extremely limited period of installation. Typically, paintings are done in much slower pace. But for this particular project, I had to complete it within a week, which required me to come up with an entirely new concept. I also had to hire an assistant for the first time. To meet the tight deadline, I aimed to keep my drawings simple, so that they can complement, rather than compete with, the oil paintings. I first created drawings that included all the necessary representational elements with selected color choices, which I then transferred onto the wall.

![Jina Park, The Long Evening, 2007. Oil on canvas. 168 x 180 cm (66.1 x 70.9 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Jina Park, Happy New Night 03, 2019. Oil on linen. 130 x 185 cm (51.2 x 72.8 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Jina Park, Happy New Night 05, 2019. Oil on linen. 170 x 140 cm (67 x 55.1 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

![Jina Park, Light, 2023. Oil on linen. 100 x 75 cm (39.4 x 29.5 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

Shifting gears slightly, another aspect of your work that has caught my eyes is your use of light. In works like The Long Evening (2007), Rehearsal 02 (2017), or Happy New Night series (2019), I notice elements of artificial lighting set against dark backgrounds. While light typically serves to illuminate subjects in reality, in your work, it becomes the focal point itself.

As you know, many of my works depict interior spaces of museums or galleries where natural light is relatively scarce within white cube. Consequently, I found myself increasingly drawn to depicting artificial lighting, which gradually gained prominence in my pieces. Exploring artificial lighting heightened my awareness of light, both in its essence and as an artist, allowing me to directly manipulate it to create various effects—an aspect I find very enjoyable.

Perhaps due to the prominence of artificial lighting outdoors during nighttime, I naturally began using this time frame more frequently as a background setting relative to daytime. There's also the unique atmosphere of the night that I wanted to capture and depict.

![Jina Park, Installation View of (left) Airport Grey by the artist and (right) Terminal Night by Peter Gahn, HITE Collection, Seoul, 2014. Photo: Sangtae Kim. Courtesy of the artist and HITE Collection]()

Has it ever occurred to you that the presence of a frame in painting is both essential and limiting? In your collaborative work with the German composer Peter Gahn, Neon Gray Terminal (2014), it felt like you wanted to expand the possibilities of painting as a medium.

Frankly, collaborations between artists in painting are quite rare. That collaboration was almost the only one I had done. During the exhibit, visitors could listen to electronic music composed by Peter through speakers installed at the site while simultaneously viewing my paintings. Peter installed contact microphones behind the canvas while I painted, recording the sound of the brushstrokes. If a painting represents the visual outcome of my work, the sound was intended to convey the rhythm and texture of the brushstrokes.

For me, it was my first collaboration with another artist, and approaching my work from a sonic perspective was an entirely new experience. The inclusion of sound made the space feel expansive, even though I was only visually observing the canvas. Of course, it wasn't just raw sound; it was the result of considerable input and processes. Nonetheless, this collaboration allowed me to experience painting in a more synthetic way, significantly influencing my subsequent body of work.

When you speak of the limitations and nature of painting as a medium, indeed, they do exist. However, I find these two aspects somewhat synonymous. While the rectangular frame may impose constraints on capturing motion, it embodies the essence, something unique to painting. Consequently, I don't perceive it as limiting in a negative sense. Personally, I've found collaborations (with Peter) to be immensely helpful, as they have expanded my understanding and perception of painting, overcoming its inherent constraints.

![Jina Park, Rehearsal 02, 2017. Oil on linen. 174 x 200 cm (68.5 x 78.7 in). Courtesy of the artist]()

It's already time to wrap up the interview. Could you share some of your future plans?

Now that the exhibition in Busan is over and I have returned to Germany, I hope to take some time to prepare for an upcoming solo exhibition. I'm considering presenting some new works alongside pieces that haven’t had a chance to be properly exhibited yet. Last year, I focused on creating works that feature restaurant kitchens. Although nothing is confirmed yet, I'm thinking about exploring different approaches to themes I have previously done. At the moment, I'm open to every new opportunity.

Her works have been featured in prestigious institutions and galleries in both Korea and abroad, including the Busan Museum of Art (2023); Cheongju Museum of Art (2021); Kukje Gallery (2021); Hapjungjigu (2018); Plan.d (2015), Dusseldorf; and Doosan Gallery (2013), New York. They could be found in permanent collections of the Seoul Museum of Art, Daegu Art Museum, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s Art Bank, and Kumho Museum of Art. Park is based in Germany and Korea.

Where are you currently staying?

I'm in Nuremberg, Germany, at the moment. I usually travel between Seoul and here once or twice a year, spending about two to three months in Nuremberg. I wish I could stay here a bit longer, but most of my work is in Seoul, so it's not as easy as it sounds.

I’m sure Seoul and Nuremberg are quite different. Do you feel that difference directly influences your work?

Personally, I prefer Nuremberg for working, as the city is generally quiet and slow. Here, I’m relatively anonymous, and there’s no constant rush to be somewhere. The studio also offers more space to work. However, there are some minor inconveniences in my daily routine, like delays in obtaining necessary materials. The fact that I don’t own a car here or speak fluent German does not help. Compared to Seoul, things here require more time and cover greater distances, so to speak. Still, returning from the bustling streets of Seoul feels like a refreshing break.

You frequently use snapshots you've taken as the basis for your work. It seems like your artworks often start with observing people's lives through these images. Does the different atmosphere between the two cities also affect what you observe?

Certainly. I may not consciously perceive the direct impact, but the shift in environment makes me view my surroundings in unfamiliar ways. Just like when you return to Korea after traveling abroad for a while—suddenly, you start noticing little things that you used to overlook, you know.

Swipe to see more images

As I carefully browsed through your earlier works from the early to mid-2000s, I noticed that the emphasis on temporality, which is now quite prevalent in your recent works, was not as noticeable. By 'earlier works,' I am referring to pieces such as the Passport Photo (2000), Head (2000), or Postcard (2002) series.

Those works were created right after I graduated from graduate school. You may have noticed already, but at that time, I was deeply impressed by this one exhibition featuring the Belgian artist Luc Tuymans. His detailed expression of photographic characteristics through a painterly approach opened up vast possibilities in painting for me. It was from then on that I began working on pieces that captured brief narratives through snapshots or postcards of my surroundings.

Swipe to see more images

Another thing I noticed from works created during that time period is the four-panel composition, which I find very interesting. It seems like the beginning of your interest in the passage of time.

I personally refer to those series as the Lomography series. While it's not so common these days, there were many cheap toy cameras back then, costing around 30-40 bucks. They were simple cameras with just basic shooting functions, allowing you to roughly capture your subject. I started taking snapshots with those cameras, and I found their format quite interesting. Snapshots inherently have a casual feeling of being accidentally captured. Since they differ from precise framing and capturing, I wanted to actively utilize the characteristics of low-tech. It seemed to align well with my approach and sensibility towards painting at that time. Those cameras take four shots in one second, meaning four shots appear on one frame. So that’s when the format started to appear on my canvas.

That camera has four lenses, so it takes four shots in one second. In other words, four shots come out in one frame. I think that was when continuous shots began to emerge in my works. I don't think I was intentionally doing it; instead, I was experimenting out of interest, fascinated by the freshness of the moment and form. One might as well call it an interest in how that specific camera captured time. Looking back, I realized that many elements forming the basis of my current work had already begun with that Lomography series

Sometimes photography serves as a means of documenting the moment for archival purposes, capturing personal moments. When you capture images with your camera, what is your intention behind the lens?

To be honest, I’m not entirely sure. I guess I have both intentions. But in the past, I tended to lean more towards capturing subjective moments, viewing it as a relatively personal medium.

Swipe to see more images

What makes you feel that way?

In the past, I often drew inspiration from my surroundings and frequently depicted scenes involving my acquaintances. However, around 2010, I began creating works that delved deeper into the depiction of exhibition spaces, such as A Man Ironing in a Round Gallery (2010) or Lighting Above (2009-2010), which blend the intention of capturing personal memory with documentation. For instance, I started photographing scenes observed at venues where I presented my works, which naturally led me to record the activities of people working on-site.

Since then, my works have become more documentary in nature, and I began more and more depicting strangers, those who I didn’t know well. Of course, this doesn't mean that my recent works lack personal significance. Occasionally, my friends still make appearances, and since most of the images are based on photos I took myself, they still represent intimate moments I've experienced. However, as I assume the role of an observer who doesn't actively intervene, they appear relatively more documentary.

From those photos you’ve taken, how do you select images to transfer onto the canvas?

I primarily focus on the actions of the figures. It's somewhat challenging to put into words, but the more I observe, the more I notice certain specific movements that draw my attention. They're nothing extraordinary, just the ordinary physical gestures we perform daily, like lifting objects while working or turning our heads to look at something—movements in a fleeting moment with a hint of tension. I narrow down the images based on these movements and sort of amalgamate them. Occasionally, when get lucky, everything aligns seamlessly, and the images from the photos can be directly transposed onto the canvas. However, most of the time, the desired composition needs to be crafted. In such cases, I choose the movements I like from various photos and arrange them on a single canvas.

Swipe to see more images

That makes me think of the continuity of images. I really enjoyed the work you showed at the Busan Museum of Art, Making of Exhibitions (2023). I loved how the images extend beyond the canvas, kind of acting as a conduit to the next sequence of action installation-wise. It also reminded me of your past exhibition Sometimes it sticks to my body held at Wess last year, in a way that it expanded the canvas into the entire space.

That commission I worked on at the Busan Museum of Art is one of my most recent works. It’s been a completely new venture for me, as I had never worked on a mural before. As you mentioned, in previous solo exhibitions like those at Wess, I had tried connecting the installation space with my drawings, imbuing an installation-like feature to a painting. At Wess, Hyejeong Chang, the curator, suggested the painting the walls with bold colors from the initial planning stage. For Making of Exhibitions, which was the museum’s final showcase before undergoing extensive renovations, the goal was to reflect on the museum's history as a space for art. So, from the outset, the curator wanted me to give me the freedom to uutilize the allocated exhibition space however I wished.

As I don't often get the opportunity to use such a large space, I decided to try something entirely new. About two months before the opening, I visited the space, diligently took photos, and tried to capture as many behind-the-scenes moments as possible. Using these photos as a starting point, I created two oil paintings and installed them in a way that extended beyond the canvas, integrating them into murals.

Were there any particularly memorable moments while you worked on the commission?

Given the constraints of nature of mural painting, you are only allowed extremely limited period of installation. Typically, paintings are done in much slower pace. But for this particular project, I had to complete it within a week, which required me to come up with an entirely new concept. I also had to hire an assistant for the first time. To meet the tight deadline, I aimed to keep my drawings simple, so that they can complement, rather than compete with, the oil paintings. I first created drawings that included all the necessary representational elements with selected color choices, which I then transferred onto the wall.

Swipe to see more images

Shifting gears slightly, another aspect of your work that has caught my eyes is your use of light. In works like The Long Evening (2007), Rehearsal 02 (2017), or Happy New Night series (2019), I notice elements of artificial lighting set against dark backgrounds. While light typically serves to illuminate subjects in reality, in your work, it becomes the focal point itself.

As you know, many of my works depict interior spaces of museums or galleries where natural light is relatively scarce within white cube. Consequently, I found myself increasingly drawn to depicting artificial lighting, which gradually gained prominence in my pieces. Exploring artificial lighting heightened my awareness of light, both in its essence and as an artist, allowing me to directly manipulate it to create various effects—an aspect I find very enjoyable.

Perhaps due to the prominence of artificial lighting outdoors during nighttime, I naturally began using this time frame more frequently as a background setting relative to daytime. There's also the unique atmosphere of the night that I wanted to capture and depict.

Has it ever occurred to you that the presence of a frame in painting is both essential and limiting? In your collaborative work with the German composer Peter Gahn, Neon Gray Terminal (2014), it felt like you wanted to expand the possibilities of painting as a medium.

Frankly, collaborations between artists in painting are quite rare. That collaboration was almost the only one I had done. During the exhibit, visitors could listen to electronic music composed by Peter through speakers installed at the site while simultaneously viewing my paintings. Peter installed contact microphones behind the canvas while I painted, recording the sound of the brushstrokes. If a painting represents the visual outcome of my work, the sound was intended to convey the rhythm and texture of the brushstrokes.

For me, it was my first collaboration with another artist, and approaching my work from a sonic perspective was an entirely new experience. The inclusion of sound made the space feel expansive, even though I was only visually observing the canvas. Of course, it wasn't just raw sound; it was the result of considerable input and processes. Nonetheless, this collaboration allowed me to experience painting in a more synthetic way, significantly influencing my subsequent body of work.

When you speak of the limitations and nature of painting as a medium, indeed, they do exist. However, I find these two aspects somewhat synonymous. While the rectangular frame may impose constraints on capturing motion, it embodies the essence, something unique to painting. Consequently, I don't perceive it as limiting in a negative sense. Personally, I've found collaborations (with Peter) to be immensely helpful, as they have expanded my understanding and perception of painting, overcoming its inherent constraints.

It's already time to wrap up the interview. Could you share some of your future plans?

Now that the exhibition in Busan is over and I have returned to Germany, I hope to take some time to prepare for an upcoming solo exhibition. I'm considering presenting some new works alongside pieces that haven’t had a chance to be properly exhibited yet. Last year, I focused on creating works that feature restaurant kitchens. Although nothing is confirmed yet, I'm thinking about exploring different approaches to themes I have previously done. At the moment, I'm open to every new opportunity.

© 2024 Radar