YOOYUN YANG has recently gained international recognition as one of the three Korean

artists selected to participate in the 58th Carnegie International. Since then,

she has continued to make strides in her career by being represented by the

UK-based Stephen Friedman Gallery and holding her solo exhibition at Night

Gallery in Los Angeles. While her audience has expanded, the way her work

connects with our existential emotions in a grounded, down-to-earth manner has

remained consistent. Her works have been featured in various institutions

including Ulsan Art Museum (2023); National Museum of Modern and Contemporary

Art, Cheongju (2019); Amado Space/Lab (2019); Doosan Gallery, Seoul (2018); and

ARKO Art Center, Seoul (2017). With her

latest solo exhibit, Afterglow in between, at Primary Practice

in Seoul, where she presents eight of her newly released works, Radar had the

opportunity to interview her.

![Yooyun Yang, The Afterimage of at that Time, 2009. Pigment on Korean paper (jangji). 145.5 x 112 cm (57.3 x 44.1 in). Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery]()

![Yooyun Yang, Fantasy, 2012. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 97 x 130 cm (38.2 x 51.2 in). Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery]()

![Yooyun Yang, Searchlight, 2015. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 105 x 149 cm (41.3 x 58.7 in). Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery]()

From the early stages of your work, which dates to the mid-2000s, have there been any significant changes in the materials you use or the themes you explore?

I've remained consistent in using jangji* as my primary medium, but there has been a shift in the type of paint I use. Around 2010, I transitioned from bunche, a traditional Korean powdery pigment, to acrylic paint. In my early twenties, I was drawn to scenes from my imagination or dreams, but as I progressed, I began to focus on real-life moments that I had personally witnessed. Up until 2018, my work often depicted political scenes I encountered in real life or through mass media. I also metaphorically expressed the political issues I had experienced. However, there came a point when I felt the need for change. I wanted to dive deeper into existential feelings, which led up to my recent exploration of themes related to light and darkness.

*jangji refers to a form of traditional Korean paper made from bark of the mulberry tree as its base ingredient.

![Yooyun Yang, Left: 1978-2017, 2017. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 210 x 150 cm (82.7 x 59.1 in). Right: Mark, 2017. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 138 x 198 cm (54.3 x 78 in). Installation view of October, ARKO Art Center, 2017-18. Courtesy of the artist and AKRO Art Center]()

![Yooyun Yang, Manhole, 2022. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 150 x 210 cm (59.1 x 82.7 in). Installation view of RENT at Amado Art Space/Lab, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Amado Art Space/Lab]()

So your focus has shifted more from societal issues to personal, inner elements. What prompted that shift?

To be honest, my interest had been exclusively centered on painting until I completed my graduate studies. I once believed that my life was guided strictly by myself, by my own will. It was only after graduation that I came to realize that the boundaries and regulations of society, including government policies, had a profound impact on my existence. With such realization came a surge of anger and self-reflection over my ignorance throughout the whole time. With such a ‘bloated’ state of emotions, so to speak, I couldn’t think of anything else but to express them through my works.

I often describe my work process as driven by a ‘losing’ mindset, a phrase that carries double meaning in Korean; it could be used to depict the sensation of defeat, as losing in a game, or the setting of the sun. It captures the state of helplessness I experience in various aspects of my life, both as an individual and as a member of society.

As a result, I now try to focus more on my personal introspective elements that resonate with me and effectively convey them, rather than societal issues.

![Yooyun Yang, Truth, 2014. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 41 x 53 cm (16.1 x 20.9 in). Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery]()

![Yooyun Yang, What Were We Looking at, 2016. Acrylic on Korean paper (soonji). 146 x 208 cm (57.5 x 81.9 in). Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery]()

You mentioned capturing scenes from real life and translating them onto your canvas. Could you elaborate on the process you used to bridge that gap?

I have a habit of documenting my everyday life through photography, whether by taking my own photos or collecting images from mass media sources. During periods of political turmoil in Korea in recent years, I actively participated in demonstrations with a strong sense of indignation. Some of the photos I incorporated into my work were taken on-site, while others were sourced from live streams or news media. When appropriating these images, I make a concerted effort to transform the original image, adding my own perspective as a human being and an artist.

Could you explain more about transforming an image? Could it be described as removing the specificity of the figures and events depicted in the photograph, rendering them anonymous?

When I refer to photographs, my intention is not to have viewers immediately recall the events depicted in the image. Although my work originates from these photographs, my aim is to allow viewers to create a new narrative from my work and engage with their own subjective interpretations by spending a good amount of time in front of the piece. I want to avoid my work being didactic or overly politically charged. This concept is also tied to my desire to present uncanny images. Since images from mass media are accessible to an unspecified audience, I believe that transformation is the key to achieving the level of uncanniness I want.

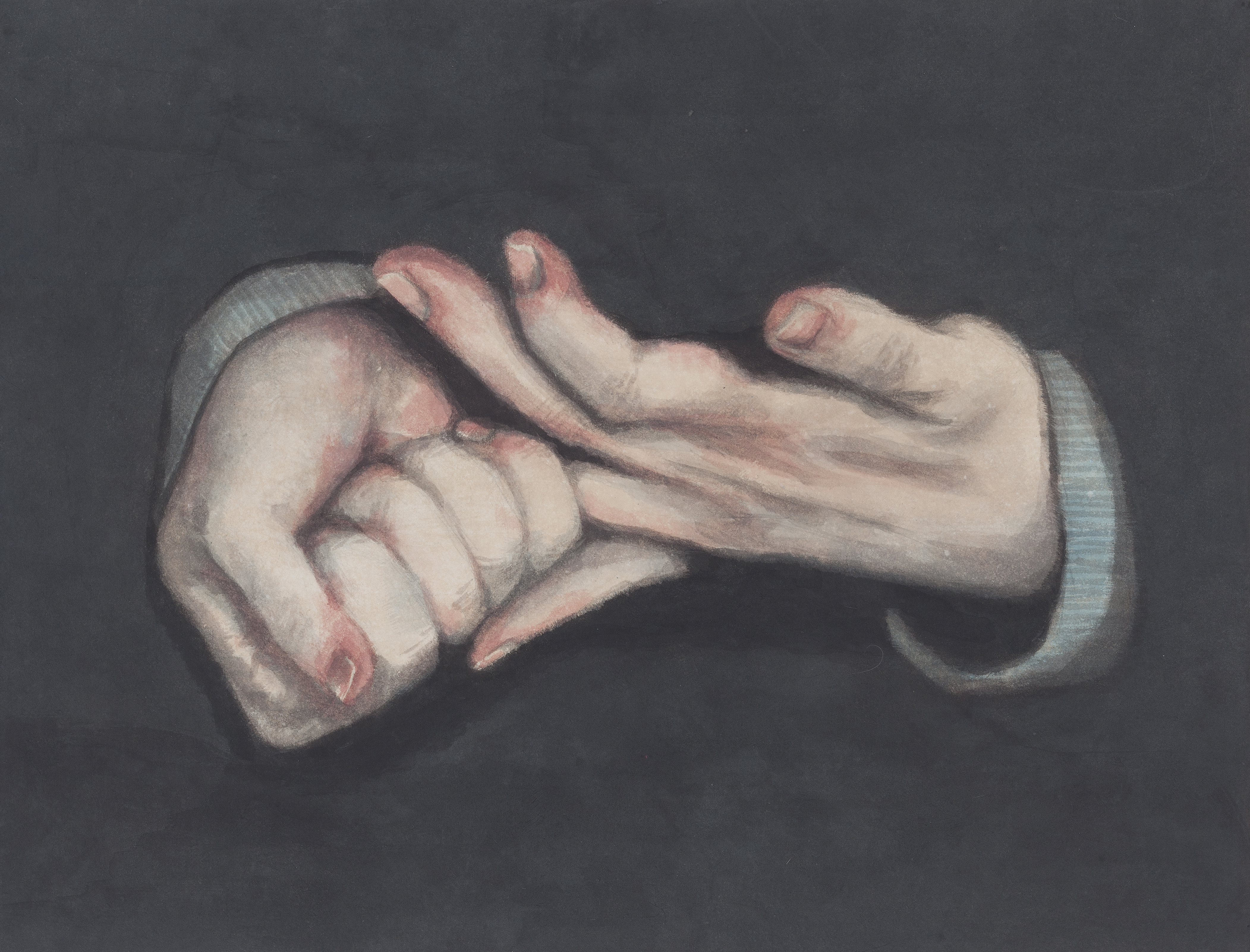

![Yooyun Yang, Tangled, 2022. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 65 x 53 cm (25.6 x 20.9 in). Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery]()

Another interesting aspect of your work lies in the cropped, close-up angle of the image, resembling a snapshot taken unexpectedly. It's as if I'm looking at a fragmented piece taken away from the broader context of a certain event.

I started using this particular angle around 2010 when I wanted to change the way I approach my work. My primary goal was to avoid having the images in my paintings appear predictable or refer to specific events. I wanted them to provoke questions about what was happening or being depicted, and to foster a feeling of doubt regarding the narrative being portrayed. This is why you might see close-ups of a palm, highlighting only the wrinkles on a hand, or an enlarged wound that blurs the line between a cut and a hole. It was also an effort to move away from conventional perspectives and subjects. I wanted to create compositions that allowed the viewer to focus on the inner elements of the depicted figure, which is why I often cropped parts of the face or body.

One aspect that captures my attention is the title – both the titles of your exhibits as a whole and those of individual works. From pieces like Distrust and Overtrust (2016) to I Know the Day Will Come (2019), and your recent show, Afterglow in between (2023), it almost feels as if one can trace the flow of your inner emotions throughout each phase just by looking at them.

I place a significant emphasis on the titles of my works and exhibits. When choosing a title, I strive to find words or phrases that convey what I'm trying to express. My personal diary or an artist's notes can be sources of inspiration, and I also revisit sentences from books I've enjoyed, tweaking them to make them my own. For me, it's essential that my works reflect my personal life and thoughts, which might explain the impression you've mentioned.

![Yooyun Yang, Passing time, 2022. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 65 x 53 cm (25.6 x 20.9 in). Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery]()

For your recent solo debut shows, Passing Time (2023) in London and Stranger (2023) in Los Angeles, I noticed the titles for both shows were in English. I assume that must have been a new experience for you.

As you mentioned, the majority of my previous works and exhibits were titled in Korean. Recently, there have been more occasions where I've had to consider them in English as well, and I've actually found this transition to be quite positive. While searching for the title, I occasionally stumble upon Korean words that hadn't crossed my mind before when translating, and at times, English terms have turned out to be more inclusive in conveying what I wish to express.

Passing Time and Stranger were both originally intended to be in English from the beginning. Passing Time, in particular, was derived from a work I created in 2022 under the same title. This piece began with a photograph of my mom’s hand that was taken while I was taking care of her while she was hospitalized. At a certain moment, I felt as though I was merely an observer of the ceaseless flow of time. I felt the phrase "passing time" was sufficient to capture the essence of the overall exhibit and convey the emotions I experienced during that particular moment.

![Yooyun Yang, Dummy, 2016. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 75 x 105.5 cm (29.5 x 41.5 in). Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery]()

![Yooyun Yang, Translucent 1, 2022-23. Acrylic on Korean paper (jangji). 210 x 150 cm (82.7 x 59.1 in). Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery]()

Speaking of Passing Time, I was delighted to see the return of the mannequin as a motif in your work. However, this time, it appeared in a translucent form as in Translucent 1 (2022-23) and Translucent 2 (2022), quite distinct from your previous pieces.

Mannequin was a recurring motif in my earlier exhibit, Distrust and Overtrust (2016). During that period, I was actively exploring various ways to convey human emotions through alternative means, and a mannequin struck me as a compelling choice. At the time, both on a personal and societal level, I found myself entangled in feelings of suspicion and uncertainty toward a subject I had believed I knew well. Through that motif, I wanted to convey the emotions of bewilderment and betrayal that arise when faith turns into doubt, along with the accompanying fear and sense of eccentricity that uncertainty brings.

In what ways was a mannequin an effective method for conveying these feelings?

Typically, encountering a mannequin in a store or a department display doesn't elicit negative emotions. I was intrigued by the fact that it could evoke an eerie sensation when encountered in an unexpected context. I spent a lot of time exploring this motif until I began to feel the limitations of its repetitive use, causing me to pause for a while. Then, last year, quite unexpectedly, I stumbled upon a discarded translucent mannequin right in front of my house.

At that time, my focus revolved around visual distortion and the ensuing sense of uncertainty. When I saw that mannequin, it felt like a strange déjà vu. I started documenting it through photographs and other means, and it organically found its way back into my work. The way the surroundings were reflected through its transparent surface, coupled with the image of a decapitated human-like figure abandoned in the middle of an alley, was captivating. To my surprise, when it was initially displayed in London, it garnered quite a positive reaction from viewers, which I hadn't anticipated.

![Installation view at the 58th Carnegie International, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, 2022-23. Courtesy of the artist and Carnegie Museum of Art]()

Regarding the use of jangji and themes rooted in your experiences in Korea, I always thought your works pertained to the specificity of Korean society. However, when I witnessed the positive response to your work at the 58th Carnegie International, I started to view your work in the context of universality rather than local particularity.

I felt the same way during that experience. I came to realize that the experiences I went through and the emotions stemming from them weren't confined to Koreans or Korean society in particular. Given the traditional, local material I use, I've often felt that my works were primarily interpreted in line with my major back in undergrad and grad school – Oriental Painting. While there were constant attempts to connect my major with the materials I use, there were fewer efforts to interpret what's happening within the canvas based on those materials. I feel that international audiences sometimes could be more open to approaching my work without preconceived stereotypes.

![Installation view of Afterglow in between at Primary Practice, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Primary Practice]()

I assume you must be quite busy with a multitude of exhibits scheduled to open soon. Have you had any specific thoughts or concerns about the upcoming shows recently?

Lately, I'm working on finding improved ways to display my work. Once my pieces are out there, they face a lot of risk due to the fragility of jangji and their direct exposure to the air without frames or glazing. It’s inevitable that they age as more exhibits take place. I'm not too sure at the moment whether I should maintain the current method of display and materials. I’m seeking better methods of preservation and exhibition conditions. These are the questions I'm currently having lately as an artist.

Yang’s new solo exhibition, Afterglow in between (2023) is open at Primary Practice, Seoul, through Sep 23, 2023. You can find out more information at: http://primarypractice.kr/exhibitions

Swipe to see more images

From the early stages of your work, which dates to the mid-2000s, have there been any significant changes in the materials you use or the themes you explore?

I've remained consistent in using jangji* as my primary medium, but there has been a shift in the type of paint I use. Around 2010, I transitioned from bunche, a traditional Korean powdery pigment, to acrylic paint. In my early twenties, I was drawn to scenes from my imagination or dreams, but as I progressed, I began to focus on real-life moments that I had personally witnessed. Up until 2018, my work often depicted political scenes I encountered in real life or through mass media. I also metaphorically expressed the political issues I had experienced. However, there came a point when I felt the need for change. I wanted to dive deeper into existential feelings, which led up to my recent exploration of themes related to light and darkness.

*jangji refers to a form of traditional Korean paper made from bark of the mulberry tree as its base ingredient.

Swipe to see more images

So your focus has shifted more from societal issues to personal, inner elements. What prompted that shift?

To be honest, my interest had been exclusively centered on painting until I completed my graduate studies. I once believed that my life was guided strictly by myself, by my own will. It was only after graduation that I came to realize that the boundaries and regulations of society, including government policies, had a profound impact on my existence. With such realization came a surge of anger and self-reflection over my ignorance throughout the whole time. With such a ‘bloated’ state of emotions, so to speak, I couldn’t think of anything else but to express them through my works.

I often describe my work process as driven by a ‘losing’ mindset, a phrase that carries double meaning in Korean; it could be used to depict the sensation of defeat, as losing in a game, or the setting of the sun. It captures the state of helplessness I experience in various aspects of my life, both as an individual and as a member of society.

As a result, I now try to focus more on my personal introspective elements that resonate with me and effectively convey them, rather than societal issues.

Swipe to see more images

You mentioned capturing scenes from real life and translating them onto your canvas. Could you elaborate on the process you used to bridge that gap?

I have a habit of documenting my everyday life through photography, whether by taking my own photos or collecting images from mass media sources. During periods of political turmoil in Korea in recent years, I actively participated in demonstrations with a strong sense of indignation. Some of the photos I incorporated into my work were taken on-site, while others were sourced from live streams or news media. When appropriating these images, I make a concerted effort to transform the original image, adding my own perspective as a human being and an artist.

Could you explain more about transforming an image? Could it be described as removing the specificity of the figures and events depicted in the photograph, rendering them anonymous?

When I refer to photographs, my intention is not to have viewers immediately recall the events depicted in the image. Although my work originates from these photographs, my aim is to allow viewers to create a new narrative from my work and engage with their own subjective interpretations by spending a good amount of time in front of the piece. I want to avoid my work being didactic or overly politically charged. This concept is also tied to my desire to present uncanny images. Since images from mass media are accessible to an unspecified audience, I believe that transformation is the key to achieving the level of uncanniness I want.

Another interesting aspect of your work lies in the cropped, close-up angle of the image, resembling a snapshot taken unexpectedly. It's as if I'm looking at a fragmented piece taken away from the broader context of a certain event.

I started using this particular angle around 2010 when I wanted to change the way I approach my work. My primary goal was to avoid having the images in my paintings appear predictable or refer to specific events. I wanted them to provoke questions about what was happening or being depicted, and to foster a feeling of doubt regarding the narrative being portrayed. This is why you might see close-ups of a palm, highlighting only the wrinkles on a hand, or an enlarged wound that blurs the line between a cut and a hole. It was also an effort to move away from conventional perspectives and subjects. I wanted to create compositions that allowed the viewer to focus on the inner elements of the depicted figure, which is why I often cropped parts of the face or body.

One aspect that captures my attention is the title – both the titles of your exhibits as a whole and those of individual works. From pieces like Distrust and Overtrust (2016) to I Know the Day Will Come (2019), and your recent show, Afterglow in between (2023), it almost feels as if one can trace the flow of your inner emotions throughout each phase just by looking at them.

I place a significant emphasis on the titles of my works and exhibits. When choosing a title, I strive to find words or phrases that convey what I'm trying to express. My personal diary or an artist's notes can be sources of inspiration, and I also revisit sentences from books I've enjoyed, tweaking them to make them my own. For me, it's essential that my works reflect my personal life and thoughts, which might explain the impression you've mentioned.

For your recent solo debut shows, Passing Time (2023) in London and Stranger (2023) in Los Angeles, I noticed the titles for both shows were in English. I assume that must have been a new experience for you.

As you mentioned, the majority of my previous works and exhibits were titled in Korean. Recently, there have been more occasions where I've had to consider them in English as well, and I've actually found this transition to be quite positive. While searching for the title, I occasionally stumble upon Korean words that hadn't crossed my mind before when translating, and at times, English terms have turned out to be more inclusive in conveying what I wish to express.

Passing Time and Stranger were both originally intended to be in English from the beginning. Passing Time, in particular, was derived from a work I created in 2022 under the same title. This piece began with a photograph of my mom’s hand that was taken while I was taking care of her while she was hospitalized. At a certain moment, I felt as though I was merely an observer of the ceaseless flow of time. I felt the phrase "passing time" was sufficient to capture the essence of the overall exhibit and convey the emotions I experienced during that particular moment.

Swipe to see more images

Speaking of Passing Time, I was delighted to see the return of the mannequin as a motif in your work. However, this time, it appeared in a translucent form as in Translucent 1 (2022-23) and Translucent 2 (2022), quite distinct from your previous pieces.

Mannequin was a recurring motif in my earlier exhibit, Distrust and Overtrust (2016). During that period, I was actively exploring various ways to convey human emotions through alternative means, and a mannequin struck me as a compelling choice. At the time, both on a personal and societal level, I found myself entangled in feelings of suspicion and uncertainty toward a subject I had believed I knew well. Through that motif, I wanted to convey the emotions of bewilderment and betrayal that arise when faith turns into doubt, along with the accompanying fear and sense of eccentricity that uncertainty brings.

In what ways was a mannequin an effective method for conveying these feelings?

Typically, encountering a mannequin in a store or a department display doesn't elicit negative emotions. I was intrigued by the fact that it could evoke an eerie sensation when encountered in an unexpected context. I spent a lot of time exploring this motif until I began to feel the limitations of its repetitive use, causing me to pause for a while. Then, last year, quite unexpectedly, I stumbled upon a discarded translucent mannequin right in front of my house.

At that time, my focus revolved around visual distortion and the ensuing sense of uncertainty. When I saw that mannequin, it felt like a strange déjà vu. I started documenting it through photographs and other means, and it organically found its way back into my work. The way the surroundings were reflected through its transparent surface, coupled with the image of a decapitated human-like figure abandoned in the middle of an alley, was captivating. To my surprise, when it was initially displayed in London, it garnered quite a positive reaction from viewers, which I hadn't anticipated.

Regarding the use of jangji and themes rooted in your experiences in Korea, I always thought your works pertained to the specificity of Korean society. However, when I witnessed the positive response to your work at the 58th Carnegie International, I started to view your work in the context of universality rather than local particularity.

I felt the same way during that experience. I came to realize that the experiences I went through and the emotions stemming from them weren't confined to Koreans or Korean society in particular. Given the traditional, local material I use, I've often felt that my works were primarily interpreted in line with my major back in undergrad and grad school – Oriental Painting. While there were constant attempts to connect my major with the materials I use, there were fewer efforts to interpret what's happening within the canvas based on those materials. I feel that international audiences sometimes could be more open to approaching my work without preconceived stereotypes.

I assume you must be quite busy with a multitude of exhibits scheduled to open soon. Have you had any specific thoughts or concerns about the upcoming shows recently?

Lately, I'm working on finding improved ways to display my work. Once my pieces are out there, they face a lot of risk due to the fragility of jangji and their direct exposure to the air without frames or glazing. It’s inevitable that they age as more exhibits take place. I'm not too sure at the moment whether I should maintain the current method of display and materials. I’m seeking better methods of preservation and exhibition conditions. These are the questions I'm currently having lately as an artist.

Yang’s new solo exhibition, Afterglow in between (2023) is open at Primary Practice, Seoul, through Sep 23, 2023. You can find out more information at: http://primarypractice.kr/exhibitions

© 2023 Radar